A large variety of cargoes carried in containers today – everything from ice cream to New Zealand lamb, from avocados to flower bulbs, from melons to fish – all require different specialist refrigerated care. Considering the high cost of most reefer cargoes it is important that each cargo is carried exactly according to its requirements. Advanced technical expertise; state-of-the art, well maintained specialised equipment; and constant support from shore and ship’s Cargo Care personnel at each stage of loading, stowing, carriage and discharge of the cargo is essential for proper care and maintenance required for these cargoes.

Equipment

Refrigerated Containers are of the latest design and utilise the most modern refrigeration machinery specified to provide the best in temperature control.

The maximum payloads have increased to over 27 tonnes for a 20′ unit and over 29 tonnes for a 40′ hi-cube unit. More details of the integral reefer containers can be found in the reference tables contained in this brochure and in the P&O Nedlloyd Container Guide.

Two such developments with the machinery manufacturers are:

The ‘Snap Freeze’ operation which reduces the heat input to the container during the machine defrost cycle, essential for the carriage of sensitive chilled produce;

The ‘Bulb Mode’, developed to stabilise the environment within the container and optimise the carriage conditions for bulbs and live plants. It also has potential uses with other products.

Further areas that container/reefer companies are developing to enhance the efficiency and cargo capability of the containers are:

- Improved temperature control

- Control of fresh air exchanges together with full humidity control

- Detection and removal of harmful gases

- Reduced power consumption

- Increased reliability

All integral reefer containers have the additional facility for monitoring temperatures within the cargo space, by using temperature probes connected to the data logger. These containers are approved by the United States Department for Agriculture (USDA) and by the Australian Quarantine Inspection Service for the ‘cold treatment’ of fruit.

Reefer Carriage

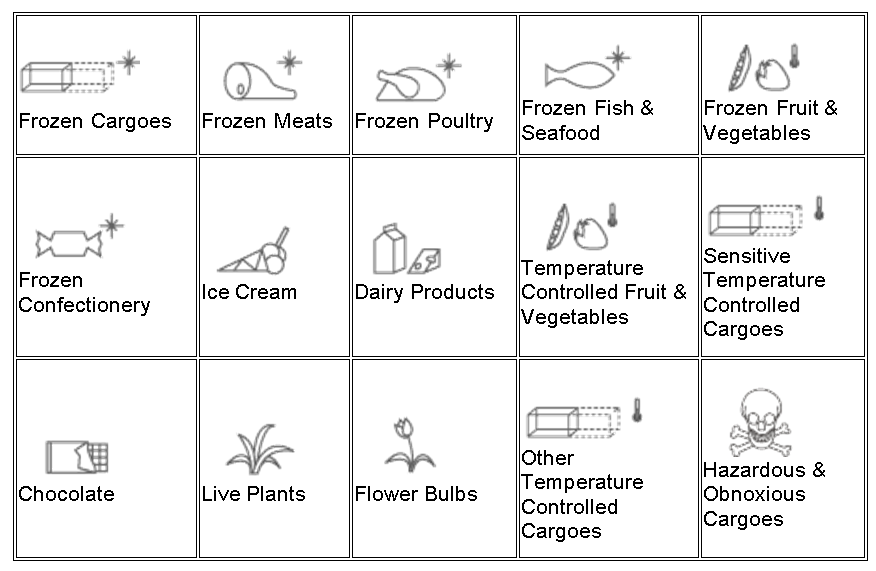

There are a wide variety of cargoes transported in refrigerated containers, all requiring unique temperature settings. These cargoes commonly range from ice cream, requiring a temperature setting of approximately – 25’C, to flower bulbs requiring a temperature setting of up to +30’C, with many cargoes in between.

Container ships carry refrigerated cargoes all over the world, travelling through climates as hot as the torrid summers of the Persian Gulf and as cold as the frigid winters of the Antarctic Ocean. The combination of the cargo temperature requirements and the climatic variations means correct temperature control of the refrigeration unit is essential, ensuring the cargo reaches its final destination in the desired condition.

Some of the cargoes carried with refrigeration

Modified Atmosphere and Controlled Atmosphere (MA/CA)

Retarding the respiration rate of fruit and vegetables is an effective means of prolonging shelf life. This can be achieved within a container by modifying the composition of the refrigerated air surrounding the cargo. Specialist containers that can control the critical mix of nitrogen, carbon dioxide and oxygen in the atmosphere are available.

Modified Atmosphere

A storage atmosphere that is different from that of ambient air, created at the beginning of the storage period, and expected to be maintained without further measurement or active control.

One – shot gas injection: This procedure involves the filling of the container with a pre-determined mixture of gases at the loading point. There is a certain degree of control over oxygen level by using the respiration of the fruit, which reduces oxygen level, and a controlled fresh air inlet port to increase the level. Carbon dioxide can be absorbed by the inclusion of lime, and ethylene by potassium permanganate or similar absorbents.

Membrane systems: they work by passing compressed fresh air over a membrane in which the fast flowing gases such as oxygen, water vapour and carbon dioxide permeate the walls of the membrane. Slow flowing gases such as nitrogen and ethylene pass straight through. In practice this means the container’s atmosphere is purged or replaced by clean, dry nitrogen. This purging action can be beneficial in flushing out unwanted gases such as ethylene and carbon dioxide. However, a large number of MA cargoes require raised levels of carbon dioxide which cannot be achieved as a result of this action. Because of the dryness of the nitrogen and the purging action humidity control is not possible. Bearing this in mind, it could be argued that these systems produce a nitrogen blanket rather than a truly exclusive container air environment.

Controlled Atmosphere

A storage atmosphere containing lower concentrations of oxygen and/or higher concentrations of carbon dioxide than ambient air that is regularly measured and its composition maintained during the storage period.

Pressure swing adsorption systems: use the selective absorption characteristics of certain minerals under pressure. By using more than one absorbent they can not only separate oxygen and nitrogen but also carbon dioxide, as required, and ethylene continuously. Instead of purging it, the gas within the container envelope is processed, thus humidity control and raised levels of carbon dioxide are possible giving a fully controlled atmosphere.

Systems tend to be more complicated and contain more components than membranes however the absorbents have to all intents an infinite life.

Packaging

Packaging is a fundamental element in the transport of temperature controlled cargoes. It is essential to protect cargoes from damage and contamination. The correct design and highest quality of materials need to be used to ensure it can withstand the refrigeration process and transit.

Where appropriate, packaging materials must be able to:

- Protect products from damage as a result of ‘crushing’.

- Be able to withstand ‘shocks’ occurring in intermodal transport.

- Be shaped to fit on pallets or directly into the container for stowage.

- Prevent dehydration or reduce the water vapour transmission rate.

- Act as an oxygen barrier preventing oxidation.

- Withstand condensation and maintain its wet strength.

- Prevent odour transfer.

- Withstand temperatures of -30’C or colder.

The wide variety of cargoes, coupled with the design and quality requirements of packaging materials, listed above, are the reasons for many different packaging types and styles.

Perishable fruits and vegetables require packaging that allows refrigerated air to circulate around the products to remove the gases and water vapour produced by their respiration.

Often cargoes are carried in cartons; these cartons must be capable of being stacked to the maximum height allowed in the container; this is approximately 2.5m (9 feet) in a hi-cube integral container, higher than most land based palletised operations. Many packaging types used for other forms of transport, for example for road haulage, may be inadequate for sea transport. Shippers are advised to thoroughly test their packaging to ensure it is suitable for transit by sea in a refrigerated container.

Equipment Operation

The ‘temperature set point’ is the temperature entered into the controller, or microprocessor, of a temperature controlled container. This determines the air temperatures supplied to the container. Nearly all refrigerated goods shipped in containers are full container loads, packed so that the ship’s officer never has an opportunity to check the temperature of the goods. Accordingly he guaranty the temperature of the goods. To carry cargo at a single ‘carriage temperature’ is impossibility, as there will always be minor fluctuations (see later).

Integral reefer containers built since early 1995 can be set between -30’C and +30’C. Special rules apply in very hot areas. Porthole containers operate with delivery air system set between -21’C and +13’C. Shippers must provide the company, at time of booking, written temperature settings, plus any fresh air ventilation requirements for their cargo.

However good the container, and however well cooled, packed, and stowed the cargo, there is of necessity a temperature gradient within the container, which is dependent on outside conditions. Such gradients are known and understood by container operators and the reason for temperature variations include: effects of ambient temperature, container thermal properties, air circulation rate, air flow patterns, refrigeration control system and loading temperatures.

Integral containers in chilled mode control the air temperatures via the supply air probe, and in frozen mode control air temperatures via the return air probe. Porthole containers are supplied with temperature controlled air from specially designed refrigeration systems aboard ships and ashore.

Some modern integral units are fitted with dehumidifiers and in-built data-loggers measuring temperatures, relative humidity and events. Digital displays allow visual monitoring of temperatures. The software installed in these integrals also prevents fans from blowing warm, moist air into the container until the refrigeration system has restarted, and the evaporator coil has cooled. This helps maintain the integrity of the temperature chain.

Some units built before 1st January 1997 and all units built since, are fitted with a special ‘bulb mode’ switch and software that can adjust the defrosting system when carrying flower bulbs and similar cargoes, thereby giving a ‘soft defrost’. Drain holes in the container floors can be unplugged, an advantage for cargoes which produce a large volume of water. All these containers can be fitted with USDA probes for the ‘cold treatment’ of fruit cargoes if required. Integral reefers are not designed to condition cargo or commodities but only to maintain the required setting temperature.

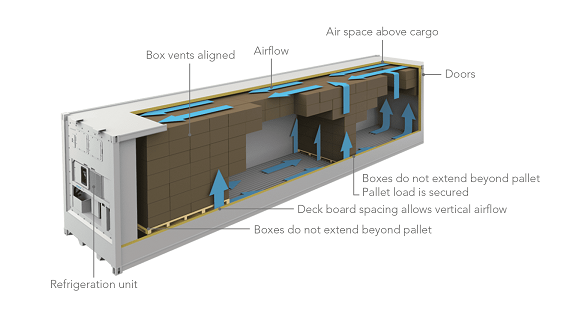

Cutaway view of an integral refrigerated container with parts identified below

| 1 | High level full width air return grill |

| 2 | Load line markings |

| 3 | Stainless steel inner linings with side wall battens |

| 4 | Evaporator/condenser centrifugal fans with motor |

| 5 | Evaporator section front face inspection panel |

| 6 | Air supply and exhaust vents |

| 7 | Gas sampling port |

| 8 | Condenser section drop down door |

| 9 | Electrical compartment |

| 10 | High and low power electrical supply cables |

| 11 | Compressor |

| 12 | Control compartment |

| 13 | Water-cooled condenser and connections |

| 14 | Delivery air plenum chamber |

| 15 | Strengthened T-section floor |

| 16 | Evaporator air movement over cooling coil and down sides of unit to form symmetrical air flow to T-section floor and through cargo |

| 17 | Delivery air duct |

| 18 | Diesel generator set locating points |

Loading Patterns

There are certain patterns that must be adhered to during loading, which will ensure the cargo is loaded efficiently and effectively for both refrigeration and transit.

Air circulation: air must circulate around the cargo to absorb the small amount of heat that enters the container through the insulated walls, ceiling, and floor. It is imperative that cargo is not loaded above the load limit line on the walls, to ensure air circulation occurs. Air must be allowed to flow between the door and the rear cargo stow, which must not extend beyond the end of the t-section floor. Any exposed areas of t-section floor must also be covered.

Space (chimneys) must not be left between pallets, or cartons, ensuring air does not short circuit back to the refrigeration unit. Gaps must be plugged with dunnage material to ensure that the maximum volume of air flows around the door area. Shippers of very small cartons sometimes cover the floor of the container with a form of hardboard that is covered with pinholes. This allows small amounts of air to flow around the cartons; this is beneficial to cargoes such as chocolate, especially if the dehumidifier in the refrigeration unit is set at 65%.

Stability and weight: cargo stability is important and shippers must ensure the cargo is well braced before closing the container’s doors. Care must be taken when opening containers in case cargo has been displaced, thus creating a safety hazard. Each country has its own maximum load weight regulations, as do the containers.

Shippers must ensure they take full advantage of the available cube space in a container, re-designing the packaging may improve the utilisation of available volume and thus reduced transport costs.

Container Preparation

Most good shipping companies perform pre-trip inspections (PTIs) on all reefer containers prior to loading. The procedure involves a physical and technical inspection of each unit to make sure the unit performs as required. Cleaning of the container involves removal of any solid matter, using hot water, detergent wash, and steam as required. The container needs to be dry before being moved to the stuffing point. Shippers must inspect and accept that each container has been supplied clean and odour free.

Pre-cooling

Pre-cooling of an integral reefer must be avoided if possible. If the temperature inside the container is colder than the temperature outside, when the doors are open atmospheric moisture will condense on the internal surfaces. The moisture will be removed once the refrigeration process begins but it will reduce the net refrigeration effect. The only exception to this is when the container is being stuffed directly from cold/chill store and the loading dock / port door is sealed against the ingress of warm moist air.

Shipper’s Responsibilities: Summary

| Item | Requirement |

| Booking | Precise commodity details Container temperature set point in Celsius Fresh air venting in cubic metre per hour (CBM) if required Dehumidifier setting as relative humidity Generator requirement if through refrigeration needed Pre-cooling of container only if appropriate Location for stuffing container and time required on site Hazardous and obnoxious materials must be declared |

| Container inspection | Verify container is sound, without visible defects, all panels secure, and is clean internally |

| Operating check if generator supplied | Set point correct, and temperature chart correctly endorsed (if fitted) |

| Pre-cooling | Check container pre-cooled, if required, when container to be stuffed through a port door |

| Stuffing | Ensure that cargo is at correct temperature and in packaging that will protect product throughout the transit. Ensure stows are below the red load limit line, and not too extended beyond the t-section floor. Air circulation through the cargo needed for respiring products |

| Delays | To be minimised and doors closed if necessary. Unstuffed cargo to be returned to store to maintain its temperature |

| Door seal | Close doors on completing stuffing and secure them with company supplied seal, record seal number |

| Legal requirements | Ensure all legal requirements including documentation for import country are completed |

| Discrepancies | Discrepancies should be reported as soon as reasonably possible. |

Diagrammatic view of the air flow inside a refrigerated container

Some recent cases of reefer cargo damage:-

Wrong orders to chill cargo

Reefer cargoes often suffer problems because of lack of adequate carriage instructions. A few typical examples given below only highlight the importance of correct temperature settings:

- Most cheeses should be carried at +4°C but some others should be carried much cooler, at -18°C or -20°C. Carrying a cheese at the wrong temperature will inevitably result in its loss. Either it will be ‘frozen to death’ or it will ripen prematurely! Normally the shipper is in the best position to know the optimum temperature for the carriage of his particular product and his reefer instructions should be followed unless they are obviously wrong or raise a natural uncertainty. But shippers can also make mistakes! In the particular case concerned, the road transporter was given the correct temperature instructions in writing. Arrangements with the ship’s agent were made by phone and the person placing the booking overlooked the fact that this particular shipment called for carriage at -18°C. There were other failures in respect of the care of the cargo, many of which arose prior to the container being received for shipment. The majority of these could have been detected at the time the container was received for shipment if sensible procedural precautions had been adopted as a matter of routine.

- A reefer container stuffed with frozen meat, suitably cooled to -22°C was loaded on board. Unfortunately the reefer list given to the master contained an error. The carriage temperature for this box was wrongly stated as being +2°C and so upon detection of the discrepancy the temperature was immediately adjusted from its correct setting to the incorrect setting specified in the list. The adjustment was made without any cross-checking of such a fundamental discrepancy and as a result the cargo arrived in the Caribbean in a state of advanced putrefaction and was a total loss.

- A consignment of live shellfish should have been transported at 0°C (which slows down their metabolism!) so that they could be delivered alive and fresh at their destination. In the absence of proper instructions being given the temperature in the containers was set at -22°C. This terminated their metabolism; they arrived at their destination deep frozen, dead and a total loss.