Many of the changes in everyday life that have taken place during the last fifty years have resulted from developments in the chemical industry. A wide range of ordinary items are in fact derived from complex chemical processes, and are often derived from the by-products of the production of energy.

The greatest advances made in the chemical industry have been made in the last 25 years. Over this period there has been a significant rise in the demand for raw materials. This in turn has led to a great increase in the maritime transportation of chemicals and the development of specialized ships in which to carry them.

The ships that have been built in response to this demand are among the most complex ever constructed. The cargoes they carry often present tremendous challenges and difficulties from a safety point of view and many chemicals are also a far greater pollution threat than crude oil.

Yet despite this, chemical tankers are among the safest ships afloat. One reason for this is the action taken by the industry and governments to adopt and implement stringent regulations regarding both safety and pollution prevention.

The chemical trade

The products of the chemical industry are all around us. Much of the food we eat is grown with artificial phosphate and nitrate fertilizers and protected with pesticide and herbicide sprays. The chemical industry has in fact transformed modern life and without it many of the products that we take for granted would never have been created.

Much of this trade is carried out by ships, but the chemical trade is very different from other bulk shipping operations. In the first place, the tonnage involved is smaller. Chemicals are shipped in relatively small amounts. A chemical carrier usually carries a variety of different products, all with different properties and, in many cases, presenting a multitude of difficulties and dangers.

Now that we know what a basic chemical carrier means we can go a little deeper.

International and national codes and regulations

Important legislative requirements governing the transport of liquid chemicals are given in:

- IBC/BCH Code, as amended.

- Marpol 73/78, as amended.

- SOLAS-1974 as amended.

- Classification society rules

- National Regulations.

Shipping activities are of international concern and that the international forum for maritime matters is the IMO, which have has adopted safety and pollution conventions that affect ships operation.

Development of regulations for carriage of chemicals

Bulk chemical codes

The subject of chemical tanker safety was first raised at the international level in the mid-1960s and it was agreed that the whole matter should be discussed by the International Maritime Organization’s Maritime Safety Committee (IMO’s senior technical body) in March 1967.

The MSC duly did so and agreed that a new sub-committee be established dealing with ship design and equipment. It should ‘consider as its initial task the construction and equipment of ships carrying chemicals in bulk.’ The new sub-committee held its first session in January 1968 and agreed to prepare a code to cover the design criteria, construction and equipment of chemical tankers.

BCH Code

Under the provisions of Annex II of the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, 1973, as modified by the Protocol of 1978 relating thereto (MARPOL 73/78), chemical tankers constructed before 1 July 1986 must comply with this Code; those built on or after that date must comply with the International Code for the Construction and Equipment of Ships Carrying Dangerous Chemicals in Bulk (IBC Code) for the purposes of MARPOL 73/78 and the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS 74).

Purpose of the new code was given in a preamble which states: ‘This Code has been developed to provide an agreed international standard for the safe carriage by sea of dangerous chemicals in bulk by prescribing the constructional features of ships involved in such carriage and the equipment they should carry with regard to the products involved.’

The Code was not, in its original form, concerned with pollution aspects. IMO was fully aware of the threat, which chemicals posed to the marine environment, but had decided to consider this aspect in the context of a new international convention on marine pollution, which was then being prepared. This was ultimately adopted in 1973 as the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL), Annex II of which is concerned with the prevention of chemical pollution.

The basic philosophy of the code is to classify each chemical according to the hazard they present and to relate those hazards to the type of ship in which they are carried: the more dangerous the chemical the greater is the degree of cargo protection and survival capability required.

The hazards considered in the new Code were:

(a) Fire hazard defined by flashpoint, boiling point, explosion limit range and auto-ignition temperature of the chemical.

(b) Health hazard defined by:

(i) irritant or toxic effect on the skin or to the mucous membranes of the eyes, nose, throat and lungs in the gas or vapour state combined with vapour pressure

(ii) irrational effects on the skin in the liquid state

(iii) toxic effect via skin absorption

(c) Water pollution hazard defined by human toxicity, water solubility, volatility, odour or taste, and specific gravity.

(d) Air pollution hazard defined by:

(i) emergency exposure limit

(ii) vapour pressure

(iii) solubility in water

(iv) specific gravity of liquid

(v) relative density of vapour

(e) Reactivity hazard defined by reactivity with: (i) other chemicals

(i) water

(ii) the chemical itself (including polymerization)

Three ship types are specified in the BCH Code.

Type 1 ships must be able to survive assumed damage anywhere in their length. Cargo tanks for the most dangerous products should be located outside the extent of the assumed damage and at least 760mm from the ship’s shell. Other cargoes, which present a lesser hazard, may be carried in tanks next to the hull.

Type 2 ships, if more than 150m in length, must be able to survive assumed damage anywhere in their length; if less than 150m, the ship should survive assumed damage anywhere except when it involves either of the bulkheads bounding machinery spaces located aft. Tanks for Type II cargoes should be located at least 760mm from the ship’s shell and outside the extent of assumed grounding damage.

Type 3 ships, if more than 125m in length, should be capable of surviving assumed damage anywhere in their length except when it involves either of the bulkheads bounding the machinery space. Such ships should be capable of surviving damage anywhere unless it involves machinery spaces if less than 125m in length. There is no special requirement for cargo tank location.

If the ship is intended to transport more than one substance, the requirements for ships’ survival correspond to the most dangerous substance, but the cargo containment requirement need only conform to the specified minimum requirements for the chemicals taken individually.

Within the ship itself other factors vary according to the hazard prescribed, such as tanks, tank vents, tank environmental control systems, electrical instruments, vapour detectors and fire protection.

The Code contains seven chapters, the first of which covers general matters such as application, definitions, surveys and certification.

The BCH Code was developed in a relatively short space of time and it was recognized in 1971 that it was far from being the last word on the subject.

The preamble to the original version says that IMO intended to either extend the code or adopt other codes to cover hazardous gases in bulk (in the event a separate code was developed); that the subject of the cargo size limitations warranted consideration; and that the section on fire protection was incomplete; and that the section dealing with electrical requirements needed to be re-examined. Work on improving the Code came to be a continuous process. Between 1972 and 1983 no fewer than ten sets of amendments were adopted, enabling the Code to be improved in many areas and to keep abreast of technical developments.

The Bulk Chemical Code, like other instruments adopted by the Assembly, was only a recommendation. There was no obligation on governments to adopt it in whole or even in part. In practice, however, the vast majority of chemical tankers constructed since the Code was adopted were built in accordance with its requirements.

At the same time it was decided that the Code itself should be further improved by bringing it into line with the Gas Code, which had been developed by IMO to deal with the construction and equipment of ships carrying liquefied gases in bulk. This was adopted in 1975, four years after the BCH Code, and was regarded as more detailed and complete.

The result was the adoption in 1983 of a new code, the International Code for the Construction and Equipment of Ships Carrying Dangerous Chemicals in Bulk (IBC Code). The Code contains the provisions of all ten sets of amendments to the original BCH Code, together with other improvements (such as a chapter on ships engaged in incineration at sea). It was agreed that the new Code would only apply to new ships (had it been made retroactive, owners of existing chemical tankers would have been faced with enormous conversion costs).

The 1983 amendments to SOLAS

There was general agreement within IMO that making the Code a mandatory instrument should end the ambiguous position of the BCH Code and that the simplest way of doing this would be by inserting an appropriate amendment into Chapter VII of the SOLAS Convention (which deals with the carriage of dangerous goods).

The IBC Code –

International code for the Construction and Equipment of ships carrying dangerous chemicals in bulk (Applicable to ships built after 01st July 1986.

The new Code was adopted by the Maritime Safety Committee in 1983 and it was agreed that it would apply to ships of any size built on or after 01st July 1986. Existing ships would still be covered (voluntarily) by the original BCH Code.

MARPOL 73/78

MARPOL, as amended, is an international convention, which contains provisions for the control of both operational and accidental pollution from ships. It has six annexes:

Annex I Regulations for the prevention of pollution by oil.

Annex II Regulations for the control of pollution by noxious liquid substances in bulk.

Annex III Regulations for the prevention of pollution by harmful substances carried by sea in packaged forms, or in freight containers, portable tanks or road and rail wagons

Annex IV Regulations for the prevention of pollution by sewage from ships

Annex V Regulations for the prevention of pollution by garbage from ships

Annex VI Regulations on the prevention of air pollution from ships.

Annex II of MARPOL

Preventing pollution by chemicals:

The International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, 1973/1978 (MARPOL 73/78) is the most important international treaty dealing with marine pollution ever adopted. Its technical provisions are contained in five annexes dealing with different pollutants. Annex II deals with pollution by noxious liquid substances carried in bulk.

Revised Annex II of MARPOL 73/78

While the MSC was working on the new IBC Code and the SOLAS amendments, IMO’s Marine Environment Protection Committee was tackling the problems associated with chemical pollution.

It had two principal objectives. The first was to amend Annex II of MARPOL 73/78 and remove the many problems associated with its implementation. The second was to modify the new IBC Code and the existing BCH Code so that they dealt with pollution aspects as well as safety.

Amendments to Annex II of MARPOL 73/78

A major problem with the implementation of Annex II arose from the original premise on which it was drafted, namely that the quantity of Category B or C chemicals remaining in a tank after unloading could be calculated using vertical and horizontal surface areas and the relevant physical properties of the substance at the temperature concerned, e.g. specific gravity and viscosity. Providing this calculated quantity was less than the upper limit established by the Convention this residue could be discharged into the wake of the ship with the proviso that the resultant concentrations in the sea did not exceed a certain limit. The application of the latter criteria required further calculations to establish a suitable speed and the under-water discharge rate for the chemical concerned. The operation of a chemical carrier with parcels of different chemicals and considerable variability of physical properties and ambient temperature conditions would mean that a member of the ship’s crew would be employed virtually full-time in computing residue quantities and ascertaining discharge parameters.

Experience indicated that the complicated procedure described above could be circumvented if the efficient stripping of tanks to a relatively insignificant residue level during unloading was made mandatory. Those smaller quantities of residues could then be discharged overboard without limitation or rate of discharge, etc.

The main purpose of the amendments to Annex II adopted in December 1985 was to introduce new pollution control provisions based upon efficient stripping of tanks.

Another major problem of Annex II concerns reception facilities, the provision of which is crucial to the effective implementation of the regulations. Reception facilities for chemicals are more expensive and complicated than those designed for the reception of oily wastes, since the wastes they are required to deal with are much more varied. There is also little opportunity for recycling them (as can be done with some oily wastes). As a result, governments and port authorities have been reluctant to provide such facilities, particularly as the Convention itself was ambiguous as to whether the facilities should be provided in loading or unloading ports.

There have been difficulties with some other aspects as well, such as developing monitoring equipment to ensure that chemicals are properly diluted before being discharged into the sea. Therefore certain operational procedures had to be developed to limit the discharge rate to minimize harm to the environment.

In 1983 the IMO Assembly had adopted procedures and arrangements for the discharge of noxious liquid substances which are called for by various regulations of Annex II and these were applied on a trial basis by a number of IMO Member States. These trials showed a number of difficulties in implementing Annex II, mainly associated with the problems already outlined in the previous paragraphs. They included:

1. The requirements were too complex and put a heavy burden on the crew of the ship.

2. Measures of control were very limited and compliance with the standards depended entirely upon the willingness of the crew.

3. There is a general lack of facilities for the reception of chemical wastes. Provision of facilities themselves did not present great difficulties because the amount is small compared with oily wastes; however, treatment of wastes and ultimate disposal was (and still is) a problem.

The tests confirmed what many authorities had already suspected and much of MEPC’s work has subsequently been directed towards improving tank unloading requirements and at the same time minimizing the need for reception facilities.

Years of work by the MEPC bore fruit in December 1985 when a special session of the Committee adopted the long-awaited amendments to Annex II. The amendments are designed to encourage shipowners to improve cargo tank stripping efficiencies, and they contain a number of specific requirements that will ensure that both new and existing chemical tankers reduce the quantities of residues to be disposed of.

As a result of adopting these requirements it was possible to adopt simplified procedures for the discharge of residues; furthermore, the quantities of categories B and C substances that is likely to be discharged into the sea has also reduced.

More studies

The IBC Code applies to all chemical tankers constructed after 1 July 1986. The BCH Code applies to other “existing” ships. The importance of the two codes is that they are concerned with carriage requirements, including the way the cargo is protected from the consequences of an accident. MARPOL’s Annex II, on the other hand, is concerned only with discharge requirements.

The Codes and the Convention are thus complementary: MARPOL is designed to prevent pollution resulting from routine operations, while the Codes help to reduce pollution resulting from accidents. Since then, work has continued on developing measures to improve the safety of chemical carriage at sea. In 1992, IMO agreed to review all the provisions in Annex II of MARPOL, with the aim of simplifying the requirements to encourage more widespread implementation of the Annex. At the same time, it agreed to review the categorization system. The decision to completely review the Annex was influenced by a number of developments.

Firstly, improvements in ship technology meant that stripping of tanks had improved to the extent that only very minimum amounts of residues would be left in tanks after unloading and consequently the limits on the discharges of substances could also be drastically cut. As improvements in technology have enabled IMO to reconsider the amount of discharge permitted to enter the marine environment, they have also provided an opportunity to reconsider the number of defined pollution categories.

Another issue was the better understanding of the environmental impact of chemicals on the marine environment. In the existing product categorization, Annex II placed considerable emphasis on acute aquatic toxicity, tainting of fish and bioaccumulation with associated harmful effects, but it was being recognized that other properties were equally important – such as chronic aquatic toxicity, and the effect on wildlife or seabed of substances that would sink or persistently float on the surface.

Annex II of MARPOL 73/78 as revised

The revised Annex II, Regulations for the control of pollution by noxious liquid substances in bulk has now introduced a new four-category (X, Y, Z and other substances (OS)) system for noxious liquid substances

The new categories are:

Category X:

Noxious Liquid Substances which, if discharged into the sea from tank cleaning or deballasting operations, are deemed to present a major hazard to either marine resources or human health and, therefore, justify the prohibition of the discharge into the marine environment;

Category Y:

Noxious Liquid Substances which, if discharged into the sea from tank cleaning or deballasting operations, are deemed to present a hazard to either marine resources or human health or cause harm to amenities or other legitimate uses of the sea and therefore justify a limitation on the quality and quantity of the discharge into the marine environment;

Category Z:

Noxious Liquid Substances which, if discharged into the sea from tank cleaning or deballasting operations, are deemed to present a minor hazard to either marine resources or human health and therefore justify less stringent restrictions on the quality and quantity of the discharge into the marine environment; and

Other Substances:

substances which have been evaluated and found to fall outside Category X, Y or Z because they are considered to present no harm to marine resources, human health, amenities or other legitimate uses of the sea when discharged into the sea from tank cleaning of deballasting operations. The discharge of bilge or ballast water or other residues or mixtures containing these substances are not subject to any requirements of MARPOL Annex II. Presently only 8 substances are included in this category, viz. apple juice, clay slurry, coal slurry, dextrose solution, glucose solution, kaolin slurry, molasses, and water.

Guidelines for transportation of Vegetable oils

Vegetable oils which were previously categorized as being unrestricted will now be required to be carried in chemical tankers. The revised Annex includes, under Regulation 4 exemptions, provisions for the Administration to exempt ships certified to carry individually identified vegetable oils, subject to certain provisions relating to the location of cargo tanks carrying the identified vegetable oils. A MEPC resolution has approved Guidelines for the transport of vegetable oils in deep tanks or in independent tanks specially designed for the carriage of such vegetable oils on board dry cargo ships. These guidelines allow general dry cargo ships that are currently certified to carry vegetable oil in bulk to continue to carry these vegetable oils on specific trades. The guidelines took effect on 1 Jan 07.

Note: Chemical tankers are generally referred to by their ship type (1, 2 or 3). This is a parameter based on a vessel’s cargo tank configuration and its ability to withstand collision or grounding damage. It gives a measure of the potential hazard of the cargoes which a ship is able to carry, e.g. ship type 2 cargoes are more hazardous than ship type 3 cargoes. (See above paragraphs for details).

Existing ship type 1 and type 2 chemical tankers will be the least affected by changes to Annex II. They will continue to be able to carry chemical cargoes and will not need any extra equipment. The cargoes, which they can carry and the tanks in which they can carry them will, however, are different. For example, vegetable oils previously carried in wing tanks will now have to be carried in ship type 2 side/bottom-protected tanks. The procedures and arrangement manual of the ship will need to be amended to take into account the new categories and the cargo list will need to be amended and reissued.

Existing ship type 3 chemical tankers will no longer be allowed to carry vegetables oils unless the ship meets certain side/bottom requirements to satisfy the vegetable oil waiver described above as per regulation 4.

Stripping tests will now be necessary for the carriage of any pollution category ‘Z’ cargoes on a chemical tanker.

Existing product tankers carrying International Bulk Chemical (IBC) Code chapter 18 cargoes will continue to be able carry these cargoes, but there will be fewer of them and most cargoes traditionally carried in large quantities, such as vegetable oils, will no longer be permitted.

Other significant changes

Improvements in ship technology, such as efficient stripping techniques, have made possible significantly lower permitted discharge levels of certain products which have been incorporated into Annex II. For ships constructed on or after 1 January 2007 the maximum permitted residue in the tank and its associated piping left after discharge is set at a maximum of 75 litres for products in categories X, Y and Z – compared with previous limits which set a maximum of 100 or 300 litres, depending on the product category. See table below.

Along with the revision of Annex II, the marine pollution hazards of thousands of chemicals have been evaluated by the Evaluation of Hazardous Substances (EHS) Working Group, giving a resultant GESAMP2 Hazard Profile which indexes the substance according to its bio-accumulation; bio-degradation; acute toxicity; chronic toxicity; long-term health effects; and effects on marine wildlife and on benthic habitats.

(GESAMP- Joint group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Environmental Protection)

Consequential amendments to the International Bulk Chemical Code (IBC Code) were also adopted, reflecting the changes to MARPOL Annex II. The amendments incorporate revisions to the categorization of certain products relating to their properties as potential marine pollutants as well as revisions to ship type and carriage requirements following their evaluation by the EHS Working Group.

Ships constructed after 1986 carrying substances identified in chapter 17 of the IBC Code must follow the requirements for design, construction, equipment and operation of ships contained in the Code.

| Pollution Category | X (Major hazard) | Y (hazard) | Z (minor hazard) | ||

| Ship type | IBC/BCH | IBC/BCH | IBC/BCH | Others | |

| Prewash requirement | Prewash | Prewash for high viscosity cargoes | |||

| Stripping requirement | BCH ships before 1.7.86 | 300 + 50 Ltrs | 300 + 50 Ltrs | 900 + 50 Ltrs | if “Z” and in IBC Ch 18, empty to max extent |

| IBC ships before 1.Jan.07 | 100 + 50 Ltrs | 100 + 50 Ltrs | 300 + 50 Ltrs | if “Z” and in IBC Ch 18, empty to max extent | |

| IBC ships after 1.Jan.07 | 75 Ltrs | 75 Ltrs | 75 Ltrs | NA | |

| Discharging requirement | Send to reception facility if > 0.1% by weight | May discharge in to sea | May discharge in to sea | ||

| Enroute criteria | >=7 kts | >=7 kts | >= 7 kts | ||

| Over board discharges | Under water (except for all ships before 1.1.07 carrying Z cargoes) | ||||

| Nearest land | >= 12 NM and >= 25 m deep | ||||

| before and after refers to the Keel laying date or conversion date |

Certification

From January 2007, chemical tankers must have new certifications and a new Procedures and Arrangements Manual. The requirement for a P&A Manual is laid out in MARPOL Annex II and the IBC Code

Classification societies will re-issue certificates to all vessels holding one or more of the following certificates, upon verification of compliance with the new requirements for the substances to be carried onboard:

- International Certificate of Fitness for the Carriage of Dangerous Chemicals in Bulk – applicable to all IBC Code certified chemical tankers carrying IBC Code Chapter 17 and, if appropriate, Chapter 18 substances;

- International Pollution Prevention Certificate for the Carriage of Noxious Liquid Substances in Bulk – applicable to all ships carrying IBC Code Chapter 18 substances only under MARPOL Annex II; and

- Certificate of Fitness for the Carriage of Dangerous Chemicals in Bulk – applicable to all BCH Code certified chemical

Before any of the new certificates mentioned above can be issued under the revised regulations:

- The Procedure & Arrangement (P&A) Manual must be reviewed and approved. Particular attention will focus on revisions to the stripping and pre-wash requirements.

- A performance test may be required, depending on the new pollution category of the substance, to verify the quantity of residue in the tank and its associated piping prior to issuing the new certificate. These tests are to be carried out in accordance with Appendix 5 of resolution MEPC.118 (52).

Ships other than chemical carriers built before 1 January 2007 which haul only Category Z substances listed in IBC Code Chapter 18 do not need to undergo this performance test as the tank and associated piping need only be stripped to the maximum extent possible.

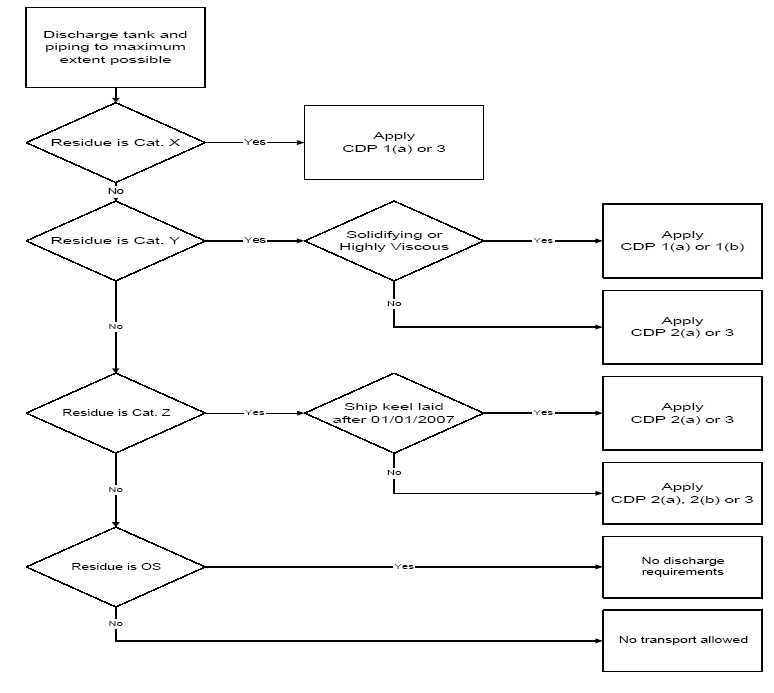

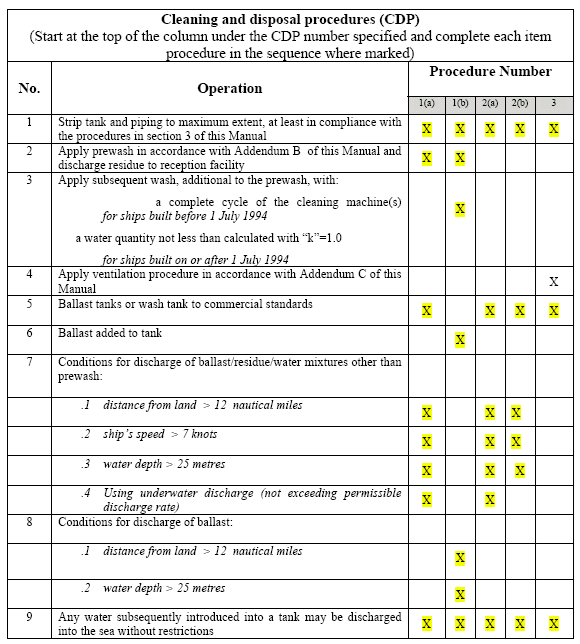

Flow diagram

This is a part of the Procedures and Arrangement manual of chemical tanker regarding cleaning of cargo tanks and disposal of tank washings/ballast containing residues of category X, Y & Z substances. It may be noted that:

1 The flow diagram shows the basic requirements applicable to all age groups of ships and is for guidance only.

2 All discharges into the sea are regulated by Annex II.

3 Within the Antarctic area, any discharge into the sea of Noxious Liquid Substances or mixtures containing such substances is prohibited.

Flow diagram of cleaning and disposal procedures (CDP) as required is shown below: