What is a liner trade and how is it different from a tramp trade

Liner trade is a trade where a ship is operated on one or more fixed routes with advertised and scheduled sailing. True passenger liners operating on ocean services were mostly displaced in the 1960s by jet airliners. Today, very few long-haul passenger liners remain and most passenger ships now operate as cruise ships.

A liner cargo vessel will accept any suitable cargo, if space permits. Most liners are container ships, ro/ros or multi-purpose (ro-ro/lo-lo) vessels. The ship’s operator may be the owners or bareboat charterers or time charterers, in which case they will be referred as disponent owners or time-chartered owner. The liner vessel’s operator is normally the performing

carrier or the ocean carrier. The carrier’s customers are shippers, who may include freight forwarders and non-vessel-operating-carriers (NVOCs) or non-vessel-operating-commoncarriers (NVOCCs) sometimes called non-vessel-owning-common-carriers.

A carrier may issue a booking note when a cargo booking is made, and will usually issue a bill of lading or a sea waybill, depending on the shipper’s requirements, as a form of receipt to the shipper of each consignment of goods, as evidence of the contract of carriage. The carrier will usually employ liner agents and/or loading brokers in order to canvass for and

book his cargoes. The carrier may be a member of a liner conference, consortium, alliance or similar arrangement, or may be a non-conference operator.

When a ship is employed in the charter market, some times called a tramp trade, the owner generally intends that she will be fixed by shipbrokers on a succession of charters. The ship may be fixed on a voyage charter market called the spot market or in the time charter market. In both the cases of voyage or time charter, the ship may be sub-chartered by the head charterer to another charterer. The ship may simultaneously be employed under a contract of affreightment.

A tramp vessel will not operate on a fixed route to an advertised schedule, except when time chartered to a liner operator. Ship owners normally employ the services of shipbrokers to fix any vessel on time or voyage charter. The master on behalf of the charterers issues the bill of

lading.

How are ships in the dry bulk and tanker market categorised

In the dry bulk shipping market the categories are as under:

• Handysize 10,000 – 29,999 dwt;

• Handymax 30,000 – 49,999 dwt;

• Panamax 50, 000 – 79.999 dwt;

• Capesize 80,000 dwt and above

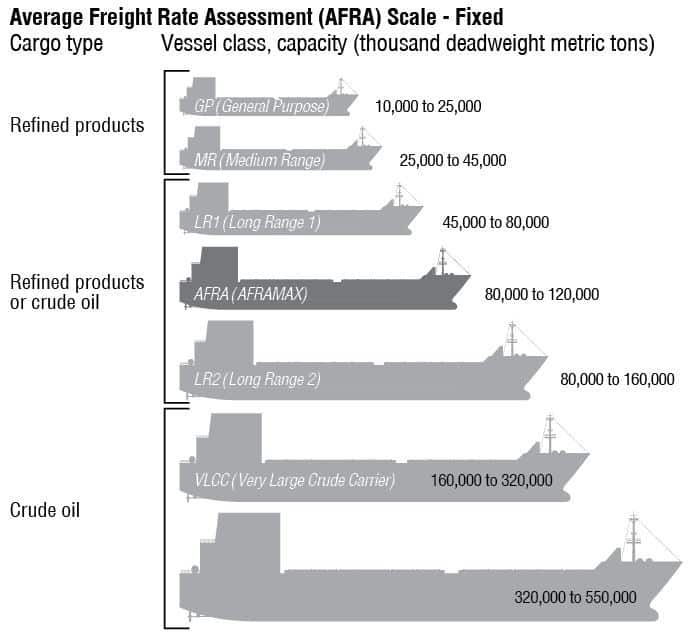

Tanker market categories are:

• Handysize 27,000 – 36,999 dwt;

• Handymax 37,000 – 49,999 dwt;

• Panamax 50,000 – 74,999 dwt;

• Aframax 80,000 – 119,000 dwt;

• Suezmax 150,000 – 200,000 dwt and she can sail through the Suez Canal when fully loaded.

Parties involved in transportation of goods by sea

The seller and the buyer are the parties contracting with each other for the delivery of the goods. Both parties agree on trade terms, which will influence the type, and terms of shipping documents (e.g. bill of lading or seaway bill). The seller may employ the services of a freight forwarder, who may the legal shipper. NVOCC operator may also be contracting for

the transportation of the goods. The carrier will issue the document evidencing receipt of the goods by the carrier (e.g. bill of lading or seaway bill) whoever the shipper is in law, to that party. In the U.S.A. the shipper is called the consignor.

A freight forwarder is a transport intermediary, who arranges the export of another party’s goods by land, sea or air and “forwards” the goods into the care of the sea carrier. Freight forwarders advise on routeing, booking space, paying freight, preparing customs documents, make customs entry, arrange packaging and warehousing etc. They also arrange goods transit

insurance, and in many cases do the groupage or consolidation i.e. converting LCL (Less than Container Load) into FCL (Full Container Load). It will have a cost-effective shipment in one transport unit of several small parcels sent by different shippers, where they are destined for

the same port or place of delivery.

A carrier is a party who contracts with a shipper for the transportation of goods by sea. In the liner trade, where NVOCC operators are offering shipping services, the carrier with whom the seller makes his contract is not necessarily the carrier actually performing the sea carriage.

The consignee is the party to whom the goods are consigned or sent by the shipper. He may the buyer of the goods or acting as an import agent for the buyer.

The receiver is the party who takes receipt of the goods from the sea carrier at the port or place of delivery. Some consignees will take direct delivery of the cargo, but in most cases they will employ a freight forwarder as a clearing agent in the customs and other formalities of importing the goods, and for transportation of goods to their ultimate destination. When loss or damage to goods is discovered on discharge, it is often the receiver who notifies the carrier.

The notify party (a term found in the bill of lading or seaway bill) is the party who must be informed by the carrier of the ship’s arrival, so that the collection of the goods can be arranged. The notify party can be a consignee or a receiver.

Banks will form links in the transport document chain when payment for the goods is being made by means of a letter of credit.

Depending on the trade terms, either the buyer or the seller will take out goods transit insurance with a cargo insurer.

FOB and CIF

FOB means Free On Board (named port of shipment) e.g. FOB Paradip. The seller must supply the goods and documents as stated in the contract of sale. He must load the goods on board the vessel named by the buyer at the named port of shipment on the date or within the period stipulated. He must bear all costs and risks of the goods until they have passed the

ship’s rail at the named port of shipment, including export charges and taxes. Risk passes when the goods pass the ship’s rail. The seller must notify the buyer when the goods have been loaded. The seller must give sufficient information to the buyer to arrange insurance: if the seller fails to give enough information, the risk stays with him. The buyer must charter the

ship or reserve space on a ship and notify the seller of the name of the ship, load port/berth and loading rate. The buyer bears all costs including insurance from the time the goods cross the rails of the ship at the load port. He must also pay the freight collectable by the carrier from the buyer at the discharge port. Seller will provide the buyer the bills of lading,

certificate of origin etc.

FOB is advantageous when the cargo is of a type or size (i.e. oil), where the buyer arranges the charter of the ship. FOB is also popular in countries with foreign exchange restrictions or where the governments want the importers to use the national flag vessels. It is used mainly for bulk sale contracts. The title of the goods does not pass to the buyer in the bill of lading until shipment is completed. FOB contract is based on the load port and the buyer after the shipment and release of the bill of lading is free to sell the goods even while they are on the vessel. FOB invoice price is lower than the CIF price. We can find FOB ST, which means free on board stowed and trimmed.

CIF means Cost, Insurance and Freight. It is a contract based on a discharge port. The seller must pay all costs including the marine insurance and freight to carry the goods to the named destination, but risk passes from the seller to the buyer when the goods cross the rails of the ship at the load port. The seller must supply the goods and pays for the carriage of the goods to the agreed port of destination, paying the freight and loading/unloading charges. He must arrange at his own expense the marine insurance policy covering the goods against the risks of carriage for the CIF price plus 10%. Any war risks insurance required by the buyer must be arranged by the seller but charged to the buyer.

The seller provides the buyer with clean, negotiable bill of lading for the agreed date of loading, an invoice, an insurance policy or certificate of insurance and a copy of the charter party if required. The seller must tender all documents to the buyer, his agent or his bank.

The buyer must accept the documents when tendered by the seller and must pay the agreed contract price. Property passes on transfer to the buyer of the documents. The buyer bears all costs and charges excluding freight, marine insurance and unloading costs unless included in the freight when collected from the carrier. The buyer must pay for the war risk insurance if

he requires it. He must effectively bear all costs of the goods from passing the ship’s rail at the port of shipment. He is protected by the insurance arranged by the seller. As the seller pays the freight the bill of lading is marked ” Freight Prepaid “. The master must ensure that the freight is actually paid before signing the bill of lading.

The buyer bears the risk during the voyage, but the title of the goods only passes, when the buyer takes up the documents. The buyer must pay when documents are received. CIF contract is more of a sale of document than a sale of goods so as to enable the negotiability of the bill of lading.

The advantage of the CIF contract to the buyer is making the seller wholly responsible for the arranging the shipment. The seller is protected against loss or damage before payment by the insurance policy. The seller can also retain title in the goods beyond the time of shipment and as security against payment by the buyer, so it is easy for the seller to obtain credit at his

bank. Goods cost more under CIF terms than FOB. In view of the advantages of the CIF terms in which the banker’s documentary credit system requires the transfer of title through the passing of the documents, a vast majority of the sea borne cargo shipments is CIF.

Documentary Credit System (DCS) between a buyer and seller of goods

DCS is a money transfer system commonly used in overseas trade to enable sellers to obtain early payment; i.e. soon after shipment of the goods. Banks check the documents carefully before they make the payments. As an example if we assume a seller in India and a buyer in New Zealand:

- Seller and Buyer conclude their sales contract, specifying payment by documentary

credit. - Buyer instructs his bank in NZ to open a credit in favour of Seller.

- Buyer’s NZ bank verifies Buyer’s Credit-Worthiness and issues a Letter of Credit (LoC) containing terms of the credit i.e. documents, times of loading etc. Buyer’s bank sends the LoC to Seller’s bank.

- Seller’s bank checks LoC requirements, then sends LoC to Seller.

- Seller despatches goods, assembles documents required by LoC, usually invoice, insurance certificate, full set of ‘clean on board’ bill of lading made ‘to order’, which are obtained once the goods are shipped. Seller presents all shipping documents to his bank and asks for payment.

- Seller’s bank checks documents against LoC requirement. If they comply including the clean bill of lading, the Seller’s bank pays Seller and sends documents to Buyer’s bank.

- Buyer’s bank checks documents against LoC. If they comply, Buyer’s bank releases documents to Buyer against payment, then reimburses Seller’s bank.

- Buyer receives documents, enabling him to obtain release of goods from ship. In case the bill of lading is claused, there could be no payments made as payment is made only against clean bill of lading.

Different charters

In the maritime context charters include:

Contracts of carriage of specified quantities of cargo in specified vessels between specified ports (Voyage Charter);contracts for hire of specified vessels, including: time charters; and bareboat charters (also known as demise charters).

(a) A voyage charter is a contract for the carriage by a named vessel of a specified quantity of cargo between named ports or places. It can be compared to hiring of a taxi for a single journey or several consecutive journeys like a consecutive voyage charters. The ship owner

agrees to present his ship (given name) for loading at a the agreed place within an agreed period of time and following loading will carry the cargo to the agreed place, where he will deliver the cargo.

The charterer, who may be the cargo owner or may be chartering for the account of another party such as a shipper or the receiver, agrees to provide for loading, within the agreed period of time, the agreed quantity of the agreed commodity. He also agrees to pay the agreed amount of freight, and to take delivery of the cargo at the destination place. In effect, the charterer hires the cargo capacity of the vessel e.g. a chemical carrier carries several parcels fixed with different charterers. Control of the ship stays with the ship owner. The ship owner pays for the wages of the crew and master, all the running and voyage costs.

(b) A time charter is a contract for the hire of a named vessel for a specified period of time, may be equivalent to a chauffeur-driven car (ship’s crew being “the chauffeur”). The charterer agree to hire from the ship owner a named vessel, of a specified technical characteristics, for an agreed period of time for the charterer’s purpose subject to agreed restrictions. The hire period may be the duration of one voyage (a “trip charter”) or anything up to several years (“period charter”). The ship owner is responsible for vessel’s running expense i.e. manning, repairs and maintenance, stores, master’s and crew’s wages, hull and machinery insurance etc.

The ship owner operates the vessel technically, but not commercially. The owner bears no cargo-handling expenses and does not normally appoint stevedores. The charterers are responsible for the commercial employment of the vessel, bunker fuel purchase and insurance, port and canal dues (including pilotage, towage etc.) and all loading/ stowing/ trimming/ discharging arrangements and costs. They direct the ship’s commercial operations, but not her daily running and maintenance. The charterers normally appoint stevedores and nominate agents. Charterer to provide the master full instructions for sailing and the master and chief engineer must keep full correct logs for inspection by the charterers. Clauses may provide for charterers to make an extra payment for hatch cleaning etc. Time charterers are normally allowed to fly their own house flag and paint the funnel and shipside their colours at their expenses.

(c) A bareboat charter (some times called charter by demise or demise charter)- is a contract of hire of vessel for an agreed period during which the charterers acquire most of the rights of the owner;

• is like a long-term vehicle lease contract;

• is mostly on the BARECON 89 charter party form;

• is used by bankers or finance houses who are not prepared to operate or manage the ship themselves;

• is often hinged to a management agreement where the owner will manage the ship for the period of charter, especially in the tanker trade;

• may be hinged to a purchase option after expiry of the charter or before (hire payment being made in instalments and transfer of ownership following the payment of final instalment).

The owner places the vessel without any crew at the disposal of the charterer and pays the capital cost and usually no other costs. The charterer pays for the technical and commercial management of the ship.

Under BARECON A form, the owner usually pays for the insurance premium. Under BARECON B form, the charterers pay for the insurance premium. BARECON B is for long term bareboat charter and mainly for newly built ships but can be used for second hand ships.

BARECON 89 is an amalgamation of BARECON A and B forms. It is designed to cater to the modern demand of bareboat charterers and shipowners. A lease agreement is a means of financing the acquisition of ship. It utilises the bareboat charter as a vehicle for loan repayment agreement. The tax benefit can be shared by agreements made besides the bareboat charter party. Normally the lessee owns a ship and on contracting for a new built

ship has a lease agreement in which he transfers the ship to a lessor. The lessor in turn gives the ship on bareboat charter back to the lessee. This allows tax benefits, which are passed on to the lessee on his payment of installations.

Sub-charter

It is common in a time or voyage charter to allow for sub-charter a ship in whole or in part, on condition that the head charterer remains responsible to the shipowner for the performance of the original charter party. It is possible therefore to have a vessel: owned by a bank or finance house;

- leased or bareboat chartered to company A;

- time-chartered from company A by company B;

- voyage chartered from company B by company C;

- employed by company C in its own liner service or even sub-chartered from company C to company D.

Any reference to a disponent owner refers to a sub-charterer, who assumes the responsibilities of a real owner.

Contract of affreightment (COA)

Contract of affreightment (COA) is essentially a contract to fulfil a long-term need for transport of especially bulk cargoes like iron ore or coal. It is an agreement between the shipowner, disponent owner or carrier for the carriage of a specified large quantity of cargo between specified ports over a specified period of time. The type and size of the ships to be used are to be stipulated by the charterers and nominated by the owners. The total period of charter is defined in the initial stage, but the shipment dates are kept flexible giving it an even spread of time e.g. every three months etc. The minimum quantity to be loaded every voyage is stipulated giving an option e.g. 20000 tons 5% MOLO (more or less owner’s option) or MOLCO (more or less charterer’s option).

COA may be based on a standard charter party with additional rider clauses, supplemented by separate voyage charter party for each voyage.

The duties and responsibilities of a shipbroker

A shipbroker is the normally the negotiator for “fixing” a ship between a shipowner and a charterer. But the term includes the following:

- Owner’s brokers, who find and arrange employment of their principle’s ship;

- Charterer’s brokers, who find ships for their principal’s requirements;

- Tanker brokers, who arrange oil cargo fixtures for the specialised oil trade;

- Coasting brokers, who work for short sea trade;

- Ship’s agent, who are employed by the shipowners or charterers to service the ship in a port;

- Sale and purchase brokers who buy and sell ships and if required arrange new buildings for a shipowner.

There are several steps in a ship fixing process:

- Cargo orders from charterers or shippers looking for a ship;

- Circulation by owners’ broker of position list or tonnage list detailing expected open dates and positions of ships;

- Study of market report by brokers;

- Negotiations of main terms with offers and counter offers;

- Negotiations “on subjects” e.g. subject stem or subject receiver’s approval etc., where the main terms have been agreed but the final agreement is subject to various secondary agreed terms;

- Fixture, where the final terms and conditions are fully agreed and all subjects lifted. Follow up of a fixture is called post fixture and a good shipbroker ensures the close post fixture working of the ship not only for his future relationship with the parties concerned but also for the brokerage amount he has to receive from the shipowner or the charterer.

Salient clauses of a voyage charter party?

The basic provisions of a typical voyage charter party are:

- Preamble – which identifies the parties to the C/P, name of the vessel, her present position and ETA load port (named) with the obligation to proceed to the load port, amount and nature of cargo to be loaded, obligation to proceed to discharge port (named) and deliver the cargo.

- Owner’s responsibility – which states owner’s liabilities or exclusion thereof in case of loss, damage or delay in delivery of cargo.

- Deviation – gives the liberty to the ship to call any port in any order and to save life or property.

- Freight – gives the rate per W/M, amount and payment of freight.

- Loading/ discharging costs – states who is responsible for the loading/ discharging costs of the cargo.

- Laytime – gives the duration of the laytime allowed, exception to the laytime, commencement of laytime and time and manner in which to tender a NOR.

- Demurrage – states the duration of the demurrage period allowed and whether it is allowed in the load and/ or discharge port.

- Lien – whether the owner can have a lien on the cargo for freight, dead freight, demurrage and/ or detention and whether the charterers are to be responsible for the freight and demurrage etc. incurred at the discharge port.

- Bills of lading – gives the master’s obligation to sign the bills of lading.

- Laydays and cancelling – states the conditions under which the charters have the option to cancel the charter.

- General Average – gives the rules under which GA can be settled.

- Agency – owner’s or charterer’s obligation to appoint agent at loading and discharge ports.

- Brokerage – amount of brokerage payable and parties thereof.

- Strikes – in case of strike or lockout fulfilling the obligation as per CP, the responsibilities for the consequences.

- War Risks – liberty of owner to cancel charter in case of outbreak of war, liberty of master to sail from load port before completion of loading in the event of outbreak of war.

- Ice – liberties of master in case of inaccessibility to a load or discharge port due to ice.

- Clause Paramount – identity of liabilities applying to bills of lading issued.

- New Jason Clause – protection of owner against U.S. lawsuits where General Average is to be adjusted in accordance with U.S. laws.

- Both To Blame Collision Clause – protection of owner against U.S. law in case of collision.

- Law and Arbitration – jurisdiction to which any dispute to be referred i.e. place of arbitration and appointment of arbitrators.

What is “World Scale” and how is it used for reference to fix a tanker on charter

World Scale is the code name for the “ New Worldwide Tanker Nominal Freight Scale “, published by Worldscale Association (London) Limited and the Worldscale Association (NYC) Inc., which are controlled by panels of leading tanker brokers in London and New York City respectively.

Oil cargo may be bought and sold many times while being carried at sea. The cargo owner therefore will need great flexibility in his discharge options. Unlike a dry cargo fixture, where the sea passage and other expenses are recalculated for a different route/ port, tanker fixtures

are based on a standard and deviation from that standard in percentage terms. This avoids the problems on recalculation every time the ship has to change its route or port of discharge.

Worldscale provides a set of nominal rates designed to provide roughly the same daily income irrespective of the port of discharge.

Worldscale is a schedule of nominal tanker freight rates used as a standard of reference by means of which rates for all voyages and market levels in the crude and oil products tanker trades can be readily compared and judged. This makes the business of tankers on charter easier, quicker and more flexible.

Worldscale is based on an average vessel with average costs earning an average rate. It works on the basis that, using the realistic costs of operating an imaginary standard tanker of ‘average’ size on an ‘average’ 15,000 miles round voyage, the break-even freight rate on that route for that ship can be worked out. This Worldscale Flat rate is calculated in USD per metric ton of cargo carried on a standard loaded voyage between a loading port and a

discharge port with a ballasted return voyage. The standard vessel is of 75,000 dead weight with an average service speed of 14.5 knots and consumption 55 m.t. of 380 CSt fuel per day while steaming, plus 100 m.t. per round voyage for other purposes and an additional 5 m.t. in each port in the voyage. Port time allowed is 4 days for the voyage. On an assumption of the vessel is on time charter, the fixed hire is taken as USD 12,000 per day. Bunker prices are assessed annually by the Worldscale associations and are based as well for the port charges on the previous year’s average. Average exchange rates for the previous September is used.

The total voyage costs divided by the cargo tonnage will give the Worldscale Flat rate or “W100” for that voyage.

From the Worldscale Flat rate, the Associations calculate the different rates for about 60,000 other key tanker routes and list them daily in a schedule made available to those who subscribe for it. Steaming distances, Suez and Panama Canal transit dues, port charges, bunker price differences between ports and various other factors mean that, in order for the ship to break even, some routes will require a higher freight rate than others. A voyage from Rotterdam to Wilhemshaven from Mina al Fahal (via Suez) will be listed as 12002 miles and may on a given date have a Worldscale Flat rate of USD11.08, while the same voyage via Cape of Good Hope (21642 miles) will be listed as USD17.37. These published Worldscale Flat rates are used for tanker charter negotiations.

It is customary in the tanker chartering market to express freight levels as percentage of the published Worldscale rates, a method known as “ points of scale”. Thus “Worldscale 100” or “W100” means 100 points of 100% of the published rate or the published rate itself. W250 means 250% of the published rate. Economic of scale dictates that a large tanker carrying large quantity of oil will have less freight rate per ton to break even in a similar voyage to a small tanker carrying less oil.

A VLCC may therefore be quoted as W41, whereas a 50,000-tonner will have W150 or more. In a fixture the negotiated freight rate will depend on the market fluctuations, but the basis for the negotiation will be the “Worldscale Freight Rate”.

Examples of tanker fixture can be:

Persian Gulf to Singapore M.T. Nilachal Express 255,000t, W42.5 January 5 (Lanark Oil).

Salient features of a time charter party

- Preamble – identifies the parties charterer/ shipowner and gives full details of the ship, her present position etc.

- Period/ port of delivery/ time of delivery – period of hire, port and time of delivery to charterer.

- Trade – legalities of trade, legalities of cargoes carried, safety of ports used and prohibition of cargoes injurious to ship.

- Owners to provide – owners’ obligation to pay for specified items.

- Charterers to provide – charterers’ obligation to pay for specified items.

- Bunkers – charterers’ obligation to buy bunkers R.O.B. at delivery port, provide specified bunkers to vessel, owners’ obligation to buy bunkers R.O.B. at redelivery port, minimum quantity of bunkers to be on board on redelivery.

- Hire – charterers’ obligation to pay hire at the specified rate, at specified intervals until redelivery; giving owner the right to withdraw vessel for default in hire payment.

- Redelivery – charterers’ obligation to redeliver vessel in same condition as when on delivery (fair wear and tear accepted), redelivery place/date/time, notices required to be given.

- Cargo Space – agreement on giving the entire cargo space of ship at charterers’ disposal.Master – to execute the voyage speedily, master and crew to assist the charterer, master’s compliance with charterers orders relating to vessel’s employment, agency etc., charterers

indemnifying owners and his servants on signing B/L or any other documents or complying with charterer’s orders, exclusion of owner’s liability for cargo claims, owner’s agreement to investigate charterer’s complaints about crew. - Direction and Log – charterers’ obligation to provide master with voyage instructions and information, obligation of master and engineers to make voyage logs available to charterers and their agents.

- Suspension of Hire – suspension of hire payment for any duration of “downtime” of the vessel in specified circumstances, charterers responsibility for loss of time in specified circumstances.

- Cleaning Boilers – owners’ responsibility to clean boilers with vessel in service, if possible, charterers’ obligation to allow boiler-cleaning time where necessary, suspension of hire when boiler-cleaning time extends beyond a specified time.

- Responsibilities and Exemptions – conditions under which the owners will be responsible for delay in delivery, delay during the charter, or loss or damage to cargo, owners’exclusion of responsibility in all other circumstances, charterers’ responsibility for loss or damage to vessel or owners caused by improper loading, bunkering or other acts by them or their servants.

- Advances – charterers’ obligation to advance necessary funds to master for ordinary disbursements at any port, deduction of advances from hire.

- Excluded ports – prohibition on charterers from ordering vessel to a place where disease is prevalent or which could be beyond the agreed limits of the crew agreement, or to any ice-bound place.

- Loss of vessel – cessation of charter hire from the date of loss of vessel.

- Overtime – owners’ obligation to place the vessel 24 hours in a day to charterers’ disposal and charterers’ obligation to pay overtime for crew working.

- Lien – owners’ lien for claims under the charter on cargoes, sub-freights and bill of lading freight.

- Salvage – equal sharing of salvage money after deductions of master and crew’s proportions and other expenses.

- Sublet – charterers’ option to sublet vessel, original charterers responsibility to fulfil the C/P obligations.

- War – prohibition on charterer from using the vessel in war zones or for carriage of goods which will expose her to risks of capture etc.; charterers’ responsibility to pay any war risks premiums, hire for time lost due to war like operations and increased costs due to war zone operations, liberty of vessel to comply with flag state orders during war, cancellation of charter by either party and redelivery of vessel if flag state becomes involved in war.

- Cancelling – charters’ option of cancelling charter if the vessel is not delivered by agreed date, charterers’ obligation to declare intention to cancel.

- Arbitration – reference of dispute to arbitration in Mumbai or at any agreed place, nomination of arbitrators by parties, umpire’s decision where arbitrators disagree.

- General Average – rules under which GA is to be settled; non-contribution of hire to GA.

- Commission – amount of (brokerage) commission to be paid by owners, and party to whom payable.

2 thoughts on “Charter Party”