Following receipt of a distress message your vessel is requisitioned to assist. You acknowledge the call and proceed towards the distress area. What navigational procedures would you employ to ensure your own ship’s safety while at the same time effectively moving to relieve the distress situation?

Answer: With any distress situation I would anticipate that communications

will play a major role. As such I would initially acknowledge the distress call and also establish contact with the ‘On Scene Co-ordinator’ if appropriate.

As the Master I would place the vessel on an alert status and establish an operational ‘Bridge Team’ to include the engine room being placed on ‘stand-by’.

I would instruct the Navigation Officer to carry out a comprehensive chart assessment, to include my own ship’s position and the rendezvous position of the distressed party. Close examination of any navigation hazards affecting the area together with any low underkeel

clearance areas would be prominently marked, as ‘No Go’ areas.

A radar watch would be established to include long-range scanning and lookouts would be posted in prominent positions on the vessel. A weather forecast would be obtained and the navigator would be instructed to obtain the expected time of sunset while on route towards the area.

The Bridge Team would operate under manual steering at best possible sea speed until closing the area. Manoeuvring speed would then be adopted (the speed of approach being faster than the speed of search and engagement).

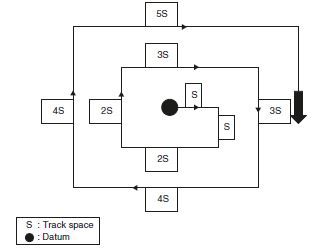

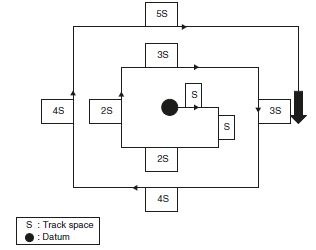

Where an area search is expected to take place, as when the ‘datum’ is unconfirmed or a wider pattern is anticipated, the Master would instruct the Navigator to plot the search area together with an appropriate ‘search pattern’.

Track space for any search pattern being determined by the relevant circumstances.

Throughout the approach the Officer of the Watch (OOW) would be monitoring the progress and position of the vessel and an effective lookout for other traffic or potential hazards would be maintained.

The echo sounder being monitored if required.

Communication updates would be ongoing and full entries made inthe ship’s log books.

What factors would determine the chosen ‘track space’ when engaging in an Search and Rescue (SAR) search pattern?

Answer: Track space for a search operation would be based on:

(a) The target definition (size, afloat Yes/No).

(b) Day or night search time.

(c) State of visibility, rain, fog, mist or snow.

(d) The likely quality of radar target presented, if any.

(e) The height of eye and prominence of lookouts.

(f) The number of surface search units employed.

(g) The searching vessels speed of operation.

(h) Recommendations from Rescue Co-ordination Centre (RCC)

and/or On Scene Co-ordinator (OSC).

(i) Recommendations from the International Aeronautical and Marine

Search and Rescue (IAMSAR) Manual.

(j) Area and intended search time before nightfall.

(k) Availability of search lights for night operations.

(l) Master’s experience.

Having recovered two survivors from a marine disaster scene, what essential questions would you need to ask them as part of your debriefing?

Answer: Following the recovery of survivors the Master of the recovering

vessel would obtain the following information:

(a) Name and rank of the survivor.

(b) Name of ship/vehicle/flight definition.

(c) Next of kin, and the address of the next of kin.

(d) Information as to cause of disaster.

(e) Total number of persons known to be aboard.

(f) Information regarding any other survivors or survival craft.

(g) Life Saving Appliance details, carried aboard the stricken vessel.

What emergency equipment would you think could reduce the period of conducting a search pattern?

Answer: The use of an Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon (EPIRB) or Search and Rescue Transponder (SART) could positively identify the targets position and reduce search time.

Other equipment such as flares, use of distress signals, etc., could also be effective if within visible range, but such items need a degree of self help and potential survivors would need to be conscious.

What are the frequencies of an EPIRB?

Answer: 121.5 and 406 MHz.

What duties would you expect to conduct when acting as an On Scene Co-ordinator in an SAR operation?

The essential function of the OSC is to provide a communication platform between the search units, the Rescue Co-ordination Centre and other interested parties.

Essential activities would include:

(a) Maximising the information on the target and plotting the ‘datum’ from all the known evidence.

(b) Establishing the position and status of all search units.

(c) Advising each search unit of the co-ordinates of respective search areas.

(d) Maintaining a detailed running log of events to include communications, weather reports, search results, updates and outcomes.

(e) Plot search units operations and their endurance capability.

(f) Request resources from relevant authorities, i.e. helicopter assistance or survival equipment.

(g) Debrief survivors and amend search plans on updated information.

(h) Allocate and guard communication channels.

(i) Disperse weather reports and/or navigation warnings to search units.

(j) Direct and co-ordinate activities to return survivors to a safe haven.

What type of facilities and conditions would suit a vessel to act as OSC?

Answer: The ideal vessel for the role of On Scene Co-ordinator would be equipped and capable of carrying out the required duties and would require the following:

(a) Adequate communication facilities on board.

(b) Sufficient manpower available.

(c) No commercial/cargo commitments.

(d) Plotting capability.

(e) No endurance restrictions.

(f) Speed overall (though this, like proximity of position, is not necessarily

detrimental).

(g) Experienced Master.

Note: The ideal vessel that is considered most suitable for the role of OSC is of

course the warship. It is in possession of all or most of the above requirements.

It is also pointed out that the role of co-ordinator is not that of a search and recovery unit. As such it does not need the rescue or medical facilities that search units need to have available, unless it is acting in a dual role of OSC and search unit.

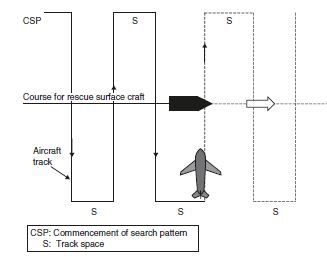

How would you carry out a co-ordinated surface search?

Answer: A co-ordinated search involves surface craft and aircraft working in conjunction with each other. Fixed wing aircraft cannot normally land on the surface but they can often effect location quicker because of the increased air speed. However, with communication to a surface craft, recovery can be effected that much sooner.

Your vessel is a high sided car carrier and while engaged in an SAR operation you locate a liferaft with four survivors. The

weather conditions are gale force 8, increasing 9. How would you effect

recovery of the survivors?

Answer: The weather conditions would prohibit the launching of the rescue boat on the grounds that it would be unsafe for my own boats crew. Under the circumstances I would order the Chief Officer to make the lifeboat ready for lowering to the water, but order the hooks

for the falls to be moused.

I would manoeuvre the vessel in order to

create a ‘lee’ for the liferaft and on the same side, lower the boat to the waterline. With heaving line assistance order the boats crew to draw the liferaft alongside the lifeboat.

Transfer the raft occupants into the boat and by using the life-boat as an elevator, recover the boat and survivors to the embarkation deck.

Note: Prior to re-hoisting the boat, the raft would need to be destroyed by a knife to all the buoyancy chambers.

How would you determine that a ‘port of refuge’ was satisfactory for your vessel?

Answer: The practical aspects of choice of a ‘port of refuge’ would be determined by the size of the port, the available depth of water inside the port and the respective underkeel clearance for the vessel to

be able to enter and berth.

Additional, preferable features of such a port would include, shelter afforded to the effected vessel and whether the port had repair facilities capable of rectifying any defects to the ship.

Answer: In these circumstances where there is no possibility of instigating repairs I would immediately make a MAYDAY with only 8 miles distance of the shore line. I would also request the assistance of a ‘tug’.

It would be my intention to reduce the rate of drift towards the shore, while awaiting the tugs arrival, by taking the following actions:

(a) Ballast the fore end of the vessel to increase the windage aft. This would hopefully present the bows to the wind and reduce drift.

(b) Walk back both anchors to provide drag effect and slow the drift.

(c) If the depth reduced to shallows I would consider use of anchors for emergency holding off.

(d) Order the Chief Officer to prepare a suitable towing arrangement (probably a composite tow line).

(e) Communications to include informing owners, obtaining weather forecast and Coastguard Authority.

Having made a distress call, what must you do once the distress situation is relieved?

Answer: Once the distress situation is resolved the distress communication

must be cancelled.

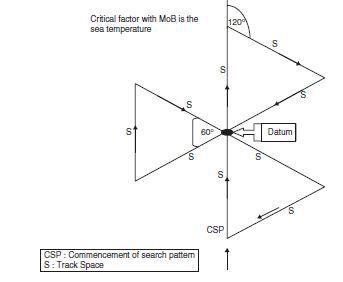

Following the loss of a ‘man overboard’, you take the ‘conn’ and complete a Williamson Turn manoeuvre but are unable to locate the man in the water. What would you now do?

Answer: Legally I am obliged to carry out a search of the immediate area. To this end I would conduct a ‘sector search’, as recommended by the IAMSAR Manual. During this period I would keep the RCC

appraised of my activities and the results of any findings.

In the event that you would have to beach your vessel, in order to prevent a total constructive loss, what ideal conditions

would you prefer?

Answer: Beaching the vessel is an extreme action and would not be carried out if an alternative action to save the vessel was available. It is an action which is employed to save the hull, with the view to instigating repairs and to re-float at a later time with improved conditions.

The ideal conditions for a beaching operation should include all or as many of the following conditions:

(a) A daylight operation.

(b) A gentle slope to the beach at the point of taking the ground.

(c) A rock-free ground area.

(d) Sheltered from prevailing weather.

(e) Current-free and/or non-tidal situation.

(f) Surf free.

(g) Communications into and out of the beach area.

Assuming that your vessel is in a damaged condition and you have just beached the ship. What would be your immediate

actions?

Answer: My subsequent actions on taking the ground will largely be dependant on what I was able to do on running in to the shore line.

Assuming that the prevailing conditions did not lend to any positive actions, I would:

(a) Order the Chief Officer to walk back both anchors to prevent accidentally re-floating off the ground into a deep water

predicament.

(b) Order the Chief Officer to obtain a damage assessment, to include a full sounding of all the ship’s tanks.

(c) Order the Navigator to obtain the tidal data for the next few days, paying particular attention to the heights and times of high and low waters.

(d) Open up communications with owners/agents with the view to instigating repairs. Cause an entry to be made in the Official and Deck Log Books.

(e) Order the crew to establish an oil boom (barrier equipment required) around the perimeter of the vessel.

(f) In the event barrier equipment is not available, make an improvised boom with mooring ropes.

(g) Ascertain the depth of water around the propeller.

(h) Add additional ballast to the ship to reduce the possibility of uncontrolled movement of the vessel.

(i) If and when appropriate, have tugs ordered to stand-by, especially so for when any attempt to re-float is to be made.

(j) Inform the Marine Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB) as soon as practical by use of an Incident Report Form.

(k) Display the appropriate ‘aground signals’ while on the beach.

(l) Inspect the lower hull and the associated ground area at low water time by boat if necessary, in order to complete the damage inspection.

While on passage on a Northerly course, West of the Portuguese coastline, your vessel encounters a fishing vessel on fire.

Four (4) men are seen on the foc’stle head frantically waving their arms.

Flames and smoke are seen coming from the aft part of the ship and the flags November/Charlie (NC) are seen flying from a midships halyard. The weather conditions are NW’ly force ‘8’. What action do you take?

Answer: The vessel indications are showing three international types of distress signals and as such, I would attempt to effect recovery of the men on board the fishing boat.

If the weather had permitted (force 6 or less) my first action would be to launch my rescue boat. In force, gale ‘8’ conditions, I would consider that such action would endanger my own crew and I would

consider an alternative method of recovery.

Such alternatives could involve the use of the rocket line throwing apparatus in conjunction with a messenger and hawser connected to:

(a) the liferaft of the fishing vessel (if it could be employed), or

(b) the liferaft of my own ship.

Either liferaft being secured with a towing hawser and used as a means of transport between the distress vessel and the rescue vessel (operation taking place on the lee side of the rescue ship).

If the use of the liferaft was impractical I would consider manoeuvring from a downwind position to draw my own vessel alongside the fishing boat, at a point which was at the opposite end from the flames.

It would be my intention to make contact forward of my own collision bulkhead. With my increased freeboard and use of scrambling nets over the bow I would encourage the men to climb the nets and gain the security of the deck.

Note: When drawing the two vessels alongside I would not be too concerned

about causing damage to the fishing vessel, assuming that the boat was probably lost to the flames already. Should my own vessel sustain damage, this would be forward of the collision bulkhead and would be considered as acceptable if

the four men are recovered successfully.

When on a coastal passage through the English Channel the OOW reports sighting a red and white striped, round buoy on

the surface. It is identified as a submarine indicator buoy. What would you do?

Answer: As Master of the vessel I would immediately take the ‘conn’ of the vessel and establish a Bridge Team in position. I would manoeuvre the vessel to circle the buoy, keeping my engines running.

During this period I would order the OOW to establish the position of the buoy and ascertain whether it was tethered or adrift.

I would carry out a chart assessment to include the position of the buoy and note the depth in this area. Once all the information is available I would communicate to the Admiralty via the Coastguard all relevant details effecting the sighting of the buoy.

I would further operate my echo sounder, post extra lookouts and if the depth was less than 50 m, turn out the rescue boat with an emergency crew on stand-by. At reduced depth the possibility of personnel employing escape apparatus to reach the surface must be anticipated.

Additional communication may be made towards the submarine by hammer blows to the turn of the bilge. Assuming that the submarine was unable to surface the noise and vibration from the hammer action

and from the propeller activity would send a positive indication to the submarine that a vessel was at the surface.

It must be anticipated that return communication from the authorities

possibly with a relief warship in attendance, would relieve my merchant

vessel of the situation.

When carrying out an emergency steering gear test drill, what would you expect to observe and do?

Answer: Emergency steering gear drills are conducted in accord with the regulations at intervals of at least three (3) months. The drill should demonstrate control of ship’s steering from the steering flat compartment instead of from the navigation bridge. The communications between the two stations, steering flat/bridge, should also be tested and seen to be adequate. Any alternative power supply should also be operated and found satisfactory.

Once the drill has been conducted, a

statement shall be recorded in both the Official and Deck, Log Books.

Following response to a distress situation which has been resolved, you are requested to carry out a towing operation. What factors would you consider, before accepting the towage contract?

Answer: It would be necessary to check the Charter Party and the Bills of Laden, to ensure that I am permitted to carry out a towing operation.

I would further check the following:

(a) The quantity and available fuel on board my vessel to carry out the tow.

(b) Is my own cargo liable to suffer by the extended operation.

(c) Are your engines and deck machinery capable of achieving the tow.

(d) Could you still meet the Loading Port, Charter Party Clause, on time.

(e) Is the value of the towed vessel and cargo worth the effort.

(f) Owners and insurance would need to be informed as a towing operation could expect to increase premiums.

(g) Do both Masters have an agreement.

When alongside working cargo in a port in the Far East, you are informed that a tropical revolving storm (TRS) is imminent.

What options are available to you?

Answer: Any vessel, in port, in the direct path of a TRS will be limited in its options and each option would depend on variable circumstances affecting the immediate area. All options should include the following:

(a) Stopping cargo operations, closing up all hatches and re-secure cargo lashings.

(b) Remove any free surface within the vessel to improve the stability.

(c) Place the engines and crew on full alert stand-by.

(d) Continue to plot the progress of the storm.

First option – would, without doubt, be to let the moorings go and run for the open sea. The decision should be made early rather than late to avoid being caught in narrows or in the proximity of navigation

hazards.

Second option – move the vessel into a ‘storm anchorage’ if available.

Use both anchors with increased scope. Ensure the engines remain operational throughout the anchor period. Double anchor watch personnel.

Third option – remain alongside. This would not be a first or even second choice and would only happen if, say, engines were disabled and no other alternative was available. Maximise the number of moorings out, and obtain tug assistance to lay out anchors. Move the shore side

cranes away from the overhang of the ship.

Take on maximum ballast, with the view to make the vessel as heavy as possible and lift and stow the accommodation ladder.

Keep crew on stand-by and endeavour to make sure engines are operational.

While on passage in winter in high Northern latitudes your vessel starts to develop ‘ice accretion’ on the upper construction.

What action would you take?

Ice accretion is dangerous because of the additional weight which builds up high on the superstructure. Such additional weight

could well impair the vessels positive stability. Initially I would alter course South towards warmer latitudes, if possible and reduce the ship’s speed to avoid wind chill factor increasing the ice build up. I would order the Chief Officer to employ the crew to clear ice formations

overboard with the use of axes, shovels and steam hoses. I would also obtain an up-to-date weather forecast and investigate the options of re-routing the vessel. If sub-freezing air temperatures are being

experienced, I would make a statutory report to this effect under a SECURITY priority communication.

Note: Clearing ice accretion is an extremely hazardous task and must be

carried out with caution, having completed a ‘risk assessment’.

When navigating in ‘deep water’ you experience a shallow sounding which is not indicated on the chart. What would

you do?

Answer: I would order the navigator to note the position of the reduced sounding and report the same by means of the Hydrographical Note (H102), found in the Weekly Notices to Mariners and in the

‘Mariners Handbook’.

This report would be despatched to the Hydrographical Department respective of the chart being used.

Having been moored by two anchors, for some time, it is realised that the ship has swung and fouled her cables in a ‘foul

hawse’. What options are available to clear this situation?

Answer: If my vessel was highly manoeuvrable with twin propellers,

bow thrust, etc., my first choice would be to try and steam around in opposition to the turns of the foul. A second option would be to employ the services of a tug, if available, to push the vessel around, against the foul turns in order to clear them.

A further option would be to hire a barge, preferably motorised, and break the anchor cable. Lower the bare end of chain into the barge and tow or drive it around the ‘riding cable’ in opposition to the foul

turns.

If all previous options are not possible, break the ‘sleeping cable’ and dip the bare end around the riding cable, by use of easing wires.

Re-connect the ‘sleeping cable’ before the turn of the next tide.

What does the ‘emergency generator’ or emergency power supply of the vessel provide for?

Answer: The emergency power supply must be a Self-Contained Unit and is independent of an external supply. It is usually a diesel motor with own starting system situated in a position away from the main engine room of the ship.

It provides an emergency power supply to: navigation lights and essential navigation equipment, the emergency lighting circuits, bilge and fire pumps, communications and the embarkation lights for the launching of survival craft.

Your vessel has been designated to be taken under tow to a repair yard for main engine repairs. The ship will retain a skeleton crew for the passage. What preparatory actions would you take, prior to engaging in being towed?

Answer: Prior to engaging the tow it would be necessary to make up a safe passage plan for the proposed operation. I would also order a full stability check to ensure that the vessel had an adequate metacentric height (GM) throughout the voyage, assuming that the vessel would be

light and in ballast, making sure that any free surface effects were kept to a minimum. It would also be prudent to carry out all, or as many of the following actions:

(a) Seal the uppermost continuous deck, with the exception of the deck scuppers.

(b) Provide the vessel with a stern trim.

(c) Check effective communications between the towing vessel and the towed vessel.

(d) Ensure that adequate Life Saving Appliances are carried for the towed vessel.

(e) A second anchor is kept ready for emergency use (assuming that the other anchor may be employed as part of the towing arrangement).

(f) Correct navigation signals are available for day and night periods.

(g) Lock rudder amidships, if the vessel is not steering.

(h) Disengage propeller shafts to free rotate, to reduce drag effects.

(i) Close all watertight doors aboard the towed vessel

(j) Reduce the oil content in the vessel to a minimum.

(k) Have a secondary emergency towline arrangement available.

(l) Contact the respective Marine Authorities, to issue navigation warnings, regarding the passage route, through international waters.

(m) Advise underwriters, who may provide an advisory ‘Tow Master’, to assist and accompany the towing operation.

(n) Obtain a local and long-range weather forecast prior to the voyage.

(o) Inspect the towing arrangement (with a Towing Master, if present) to ensure strength and securing.

Following a collision and damage to your own vessel you are taken to a port of refuge. What must you have on board prior

to sailing from the port?

Answer: An Interim Certificate of Class. Depending on the extent of repairs it may also be necessary to ‘swing the ship’ to recalibrate the magnetic compass. In such circumstances a new deviation card would

also be required.

What safety precautions are in place to prevent accidental release of the CO2 injection system into the engine room?

Answer: The remote cabinet outside the CO2 room is fitted with a ‘break glass take key to unlock’.

Operation. Once inside the cabinet a stop valve control must be released prior to operation of the pilot bottles that activate the CO2 bottle bank.

How would you increase pressure and continue the water supply to hoses fighting an engine room fire?

Answer: Shut the isolation valve to the deck line. (Usually found on the forward end bulkhead in the engine room.)

How would you ensure your crew are trained to handle situation disasters?

Answer: Throughout the period of the voyage it would be prudent to exercise the crew in disaster training scenarios. This could be carried out during the period of boat and fire drills.

These should be active drills with personnel being interchanged to provide multiplicity on essential tasks. Disaster/safety videos could be shown to crew. Alleyways and public rooms could carry educational and advisory posters.

Reality casualty rescues, rescue boat activity inside harbour limits, together with encouraging shore side training courses would all be expected to improve the state of readiness and efficiency of the crew.

You hear a distress signal and proceed at best possible speed to the last known position of the distressed vessel. When you

arrive on scene nothing is found. What action would you take?

Answer: On approach I would have my Bridge Team in place and my vessel on an ‘alert status’ with engines on ‘stand-by’. I would have posted extra lookouts and would commence an expanding square

search pattern as per IAMSAR (Reference for expanding square search pattern: IAMSAR, Guidance to Masters on Search and Rescue Operations is also contained in the Annual Summary of Notices to Mariners,Notice No. 4).

I would inform the Marine Rescue Co-ordination Centre (MRCC) of the situation and update this report as and when evidence of the incident presents itself. Monitor my own position closely and update the weather reports, not standing my own vessel into danger