To examine Bills of Lading under International Conventions, first we should know mechanics of imports & exports, and how they affect Masters. B/L is usually an essential document required under the terms of a letter of credit. Both are negotiable instruments, and can be bought and sold.

A Bank on behalf of a buyer establishes a Letter of Credit (LC). The bank specifies on face of the LC, name, cost, specifications, description and quantity of material he is buying. Bank undertakes to pay a pre-determined sum of money “without recourse to buyer,” provided all requirements of the buyer as per UC terms have been complied with by seller IN TIME.

CIF Contract

CIF contract includes ex-factory Cost, freight and Insurance plus clearing/forwarding charges at load port. Seller insures goods, nominates the vessel and pays freight. If buyer insures goods, it becomes C & F in which case, if goods are lost/ damaged in transit, buyer claims from insurer in his own country, which is easier for him.

FOB Contract

FOB (Free on Board) contract is ex-factory price, plus Clearing, forwarding & loading costs. Buyer insures cargo nominates carrier & pays freight. Exporter must load goods on board, within date stipulated in UC, as otherwise UC expires unless buyer & his Bank extend it. With cargo on board, a B/L is issued. Exporter submits it and other documents as per UC to his bank. If all requirements as per International practice, and all terms of the UC are strictly met, bank must pay out. Bank cannot refuse payment unless all documents are not strictly as per L/C. With B/L in hand, importer takes delivery of his cargo.

Charter party

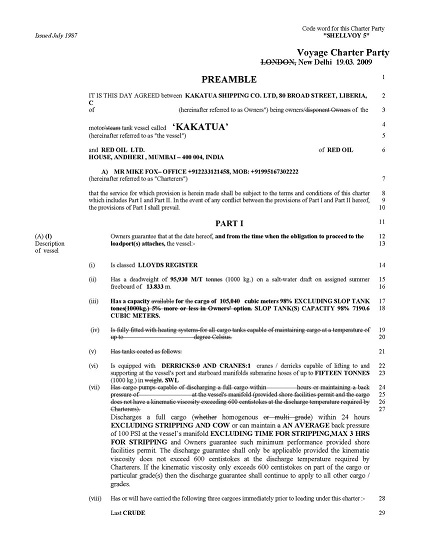

Today, Liner trade for non-bulk cargoes is monopolised by containers. But if quantities of cargo to be shipped are either in one shipload or in many shiploads, exporters or importers enter into contracts of carriage with owners. An owner lets his ship to another to carry his cargo under a Charter Party (C/P), contract.

In old days, since no copies could be made, only one document was handwritten & signed. One half of the written contract was given to each party. Thus Carta (card) PARTITA (partitioned). In Latin it means separated paper. Term ‘Carta Partita’ became known as Charter Party in time.

There are three main types of charters, which are of prime interest to Masters, namely:

► Voyage Charter

► Time Charter

► Bareboat Charter

Voyage charter

Owner places his vessel’s carrying capacity at disposal of charterer who is entitled and obliged to use all cargo space on board. Management, manning, fuel, stores, navigation etc. are owner’s responsibility. Charterer may not retain any interest in the ship once he completes loading and has received B/L (Cesser Clause). But he may have a right to nominate discharge port if not already specified & if C/P gives him that right.

If he loads short, owner is entitled to claim ‘dead freight’ i.e. “additional money he would have earned, had full cargo been loaded, carried and discharged.” Dead freight takes into account what shipowner would have spent in loading, (stevedoring costs, time used, port charges etc) carrying, (time saved i.e. more speed, less fuel) and Discharging’ (similar costs as loading). All such costs are offset against freight for short-shipped cargo to arrive at net amount payable. Master should reserve owner’s right to dead freight, furnish them with all particulars including statement of facts duly signed by the other party and let them calculate what amount is due to owners as Dead freight. Master may not usually have all information to calculate and arrive at the net amount of Dead freight payable.

Case 1

In a recent case, weather was bad and terminal authorities stopped loading after only 400,000 bbl crude was on board instead of 600,000 bbl, as per charter party. Charterer paid only $ 181,332, on prorata basis, out of agreed lump sum freight of $ 307,500. Arbitrators awarded the balance freight to owner.

Commercial Court in London, found that before Master left the moorings at load port, he was given a statement that loading was discontinued “due to prohibitive weather conditions”. Therefore failure to load a full cargo arose out of charterers’ instructions to the vessel to sail.

Charter Party imposed a mutual obligation on owner to receive the cargo and on charterer to supply it. Owner’s obligation depended on charterer performing its part of the bargain. Number of days are allowed to charterer to load and discharge cargo under C/P. Time used to load and discharge depends on port and weather conditions, delays, and availability of cargo, which is charterers responsibility subject to C/P clauses. Owners are entitled to Demurrage for additional time used by charterer. If less time is used, charterer is entitled to Despatch.

Obviously vessel can rarely load or discharge exactly within lay time allowed in C/P and some money is likely to be due to owners or to charterers under a voyage charter party. If C/P is on liner terms or F10, this is not relevant.

Equally obviously it is in the interest of charterers to present statement of facts at Load/Disch ports at the last moment so that master is not able to scrutinise it in detail. Master should ensure that charterers present statement of facts in good time before sailing, and scrutinize it well.

In cases where voyage charterer loads short, even though owner is entitled to claim Dead freight under C/P, he is also obliged in Law to mitigate his losses. It means that he cannot simply rely on his claim for Dead freight without making every effort to find other cargo for his ship, provided it is available practical, economical and reasonable for him to be able to do so.

If he succeeds, he has-to offset freight so earned against dead freight on short-shipped cargo and claims the difference from charterer who is in breach of voyage C/P.

It may happen that a voyage charter is for part cargo, say 30000 MT for a vessel of 48000 DWT. In such a case, owner usually reserves his right to complete his ship with other cargo enroute.

Time charter

Vessel is hired for a fixed period for use within agreed geographical limits and delivered to charterer at a designated place within agreed dates of delivery. Charterer is entitled to trade the vessel within agreed geographical limits. Hire is payable in advance fortnightly or monthly. Cost of fuel, Port dues, consumables stores, Towage, Pilotage etc are to charterer’s account. Manning, salaries, repairs maintenance, catering etc. are to owners account.

Bareboat charter

This is usually a long-term charter mainly and usually used when charterers want to buy the ship but wish to see her performance before purchase. Charterer has more control on the vessel, which is delivered BARE without manning, stores, provisions, fuel etc. Owner may retain his right to appoint master, but she is otherwise manned and paid for by charterer. Owner insures her. Vessel does not change her nationality and flag. But for all practical purposes the ship is under complete control of the charterer who may even change colours of her hull and funnel during the time she is under his control.

Charter party clauses

Printed and added clauses in a C/P govern rights and obligations of Owner & charterers. Some clauses should be fully understood by Master, so that he can protect interests of his ship and owner’s effectively at all times. Till very recently it was not the practice of owners to provide a copy of the Charter party to Master. But Now under ISM Code owner must do so.

Description of ship in the charter Party.

A vessel is usually described as vessel of X DWT, capable of steaming fully laden under good weather conditions, at about Y knots on a consumption of about Z tons. Kind of fuel used, may be specified. Make & type of Engine may also be included in the description. Most claims, which arise under a Time Charter, are for under performance or over consumption. To show that vessel performed as per C/P, only that speed and consumption when fully laden under good weather conditions is relevant. Evidence of less speed or over consumption claims are mostly recorded in Deck and ER log books, which are used as basic data. Allowance is made for Weather, sea state, wind direction, effect of tides and currents etc. Use of substandard or wrong fuel may cause loss of speed and/or over consumption, and damage the Main Engine. Fact that under time charter, charterer supplies fuel complicates matters.

Case 2

A Bulk carrier was described in NYPE C/P as 117,950 DWT; LOA; 264m; Beam: 40m; Main Engine B&W . She sailed from Rio de Janeiro after bunkering by charterers as per C/P. At Norfolk, excessive cylinder liner, piston ring and fuel pump wear was discovered in all cylinders. Sediment and Catalytic fine contamination analyses of sludge from scavenge space and lubricating oil purifier confirmed wrong fuel used. Vessel proceeded on diesel oil at reduced speed after repairs, till correct fuel was supplied. Owners held charterers responsible for wrong fuel supplied.

Time charterers successfully argued that as no fuel specs were exactly specified in C/P which only gave make & number of engine, They checked with manufacturers of engine and supplied bunkers as per their Specifications. Owners lost in Arbitration due to scanty description in C/P with following consequences: –

► When wrong fuel was used damages were caused to engine i.e. off hire & cost of repairs.

► Till correct fuel was supplied, vessel had to proceed on slower speed and Diesel oil. Claim for loss of speed, time and extra expense.

► When correct fuel was supplied, wrong fuel was still on board. Thus claim for loss of DWT.

► Loss as wrong fuel was sold at distress price.

► Owners lost over $100,000 in off-hire, repairs cost of spare parts, replacement of fuel, use of diesel, loss of speed, loss of DWT capacity etc.

Bunker specifications

Despite what is written in C/P, Master MUST always includes EXACT specs of oil when requisitioning fuel especially in Time Charter. Drip samples of oil should be taken, tested, marked and sealed at ship’s MANIFOLD. Master should ask supplier and charterers agents, in WRITING, to attend during drip sampling & testing.

Cesser clause:

This clause provides that charterers liability shall cease when Cargo is shipped and advance freight, Dead freight, and Demurrage if any, at load port, are paid, Owners having lien on Cargo. This is a dangerous clause when read with another clause which requires Master to sign B/L ‘as presented,’ which will usually be freight prepaid B/L.

Once signed such B/L becomes contract of carriage with 3rd parties who are strangers to the C/P. Thus if freight, dead freight & demurrage are not paid at load port, Owner cannot exercise lien on cargo. Master should either refuse to sign such B/L or endorse them with amounts due and note protest. This may help owners to collect monies due at load port and to enforce lien at discharge port.

Otherwise charterer should be persuaded to provide a letter of guarantee countersigned by his bank, for owners to encash it in the same country. Usually, a letter of guarantee issued by a national in one country is not valid and enforceable in another country because of the principle of sovereignty of nations.

Always afloat clause

A frequently used clause in C/P is: “ship to proceed to a port and there load, always afloat, a full and complete cargo of Xetc. As customary. With these words port named must be suitable for the vessel to remain always afloat. But in some ports where nature of bottom is suitable, it maybe customary for a ship to lie aground at times.

Hence words “as customary.” If possible Master should obtain independent written evidence from harbour authority that it is customary for ships of her size and draft to lie aground, while loading or discharging, and keep owners and P & I Club fully informed. Local P&l agent maybe the only one he can trust because if there are problems, liability may fall on the Club. So he is not likely to misguide the Master.

Safe Port/Safe Berth (SPSB)

A port is not safe unless in the relevant period of time, the ship can reach it, use it and return from it without, in the absence of some abnormal occurrence, being exposed to danger, which cannot be avoided, by good navigation and seamanship. A time charterer is obliged to nominate a safeport and safe berth for the ship.

Following guidelines determine a safe port/safe berth: –

► There must be safe access free from any permanent obstruction. A temporary obstruction, such as neap tide does not make an otherwise safeport or berth unsafe.

► Port/berth is safe, where a vessel can lie safely afloat at all states of tide, unless it is customary and safe to load or discharge aground, & there is written agreement to do so.

► A port or berth is not safe if, having reached, it, a vessel cannot sail out safely, e.g. without say cutting her masts, or without over ballasting. This may happen where a loaded vessel has passed under a bridge while entering harbour, but after discharge of her cargo, her air draft is too much to pass under the same bridge.

► Time at which the port must be prospectively safe is the time when the vessel will be approaching, using and departing from it. 5. If C/P specifies a range of Load/Dis ports, the nominated port must be safe for the vessel.

► Port must be politically safe, free from war or embargo. (See Kanchanjunga case below)

► Where a voyage C/P specifies a port or berth, onus is on owners to ascertain whether their vessel can safely enter, use and leave that port.

► Owners may be in breach of B/L contract if they invoke SB/SP clause in C/P unless terms of C/P are incorporated in B/L or charterers are also owners of cargo.

► A port can be safe for a ship, even though she may have to leave it when certain weather conditions are imminent. Nevertheless such port is not safe unless there is reasonable assurance that imminence of such weather conditions will be recognised and that the ship will be able to leave the port on timely warnings.

► Unless there is specific agreement, master is always entitled to refuse to enter a port, which his vessel cannot safely reach without first lightening in roadstead or another port even if that is a customary way to discharge at that port.

Case 3

A 120,000 DWT bulk carrier on time charter, arrived at nominated port in North Japan in DECEMBER. As weather deteriorated, strong northerly winds caused her to range against the quay on heavy swell. One fender unit disintegrated. Continued ranging against unprotected section of the wharf, due to pressure from wind and swell caused heavy damage to shell plating.

Owners claimed that nominated port was not safe because: –

► There was no protection from northerly winds. There was no system in operation, to provide protection alongside or for vessel to leave berth quickly if weather conditions so warranted.

► There was no satisfactory system in operation to provide warning about deteriorating weather conditions,

► Fenders alongside were inadequate and not properly equipped, for vessels of size scheduled to use the facility, as chains required to limit upward and downward movement of fenders were missing on some units.

► Berth was not provided with a system of mooring points to allow balanced and effective use of mooring ropes and wires, because it had been extended to accommodate two vessels. As a result, vessel’s stern overhung the end of berth. Stem lines led to a distant post on shore and were some three times the length of head lines, which caused excessive pressure on one fender resulting in its collapse.

Further movement brought the vessel into contact with exposed concrete, causing severe shell damage.

Arbitrators found charterers in breach of contract to nominate a Safe Port and Safe Berth. They rejected charters’ argument that weather was exceptionally severe and found that although weather conditions were unusual, they were not abnormally so, for December in Japan! Test is whether prudent Charterers should nominate that berth considering all circumstances, including location, protection and time of year.

If such weather was experienced in summer, arbitrators could have found the weather to be exceptionally severe and that charterers acted prudently in nominating that port which was normally safe at that time of they ear. But in prevailing circumstances arbitrators may have felt that prudent charterers should have taken into consideration that it was December in North Japan.

Arbitrators further rejected charterers’ argument that Master was negligent in mooring his vessel and lines had become slack. They held that Master had acted in accordance with standards of prudent seamanship.

Case 4

Kharg Island was nominated load port for last voyage of SCI KANCHENJUNGA, 272,000T, chartered for eight consecutive voyages. Owners instructed master to proceed to Kharg Island. She arrived on 23 November and gave notice of readiness On December 1, while ship was still waiting to berth, Iraq bombed Kharg Island and Master sailed away. Owners sued charterers for nominating an unsafe port.

House of Lords Held that Kharg Island was not prospectively safe when nominated, but that owners waived their right to object to the nomination by instructing Master to proceed to Kharg Island. This case has been approved in a subsequent case in England. Therefore rule is that owner is entitled to reject nomination of a port by charterer if he considers it to be prospectively unsafe. But once owner accepts the nomination, he has exhausted his right of rejection.

Case 5

In a 1993 case the “Saga Club” was chartered to be employed in Red Sea area. Vessel called at Massawa many times in 1988. In Sept 1988 Eritrean Guerrillas attacked her about five miles north east of Massawa. Court of Appeal held that on the date vessel was ordered to Massawa, it was a safe port.

Case 6

Product Star on charter to ADNATCO performed four uneventful voyages from Ruwais to Chittagong. On fifth voyage owners requested for another load port and instructed Master not to sail North of 24 Deg N.

Held that there was no evidence on which a reasonable owner could have considered that risk of proceeding to Ruwais was greater than that which existed at the time of signing the charter, which risk the owner had accepted.

Off hire/ breakdown clause

This clause provides that if time is lost in circumstances, which prevent a vessel from performing service required of her, payment of hire will cease until she is efficient to resume service. It is operative only when time is lost in rendering service required of her at THAT time. Where a ship’s main engines failed and she was towed for part of the voyage to discharge port, it was held that hire was not payable during period on tow but she came on hire when she commenced discharging at nominated port with her own gear, found efficient for that purpose. Unless he has precise instructions from owners, master should never sign any agreement to off-hire period. He should certify facts and keep owners fully informed.

Case 7

Under Time M. V. Aquacharm was ordered to load to 39 ft 6 inch, permitted Panama Canal draft, Master loaded accordingly but did not allow for Gatun Lake, when she would draw more and trim further by the head in fresh water. As she was already down by the head on arrival at Cristobal, she was refused transit. 636 tons coal was discharged into a lighter, which followed Aquacharm through the canal. Cargo was reloaded after transit.

Charterers claimed an amount of USD 86344.99 as off-hire’ for nearly 8 days delay. Held, by Court of Appeal, she was not off hire. She remained fully efficient in all respects. But could not transit Canal by being overdraft. In no way this affected her efficiency as a ship.

LORD DENNING M.R. In seeing whether clause 15 applies, we are not to inquire by whose fault the vessel was delayed. We are to inquire whether ‘full working of the vessel’ has been prevented. The vessel is still working fully, but she is delayed by need to unload part of her cargo. Working of the vessel is not considered to be hindered where she is prevented from performing her service by external causes.

In this case owners spent money to discharge and reload cargo on their own account. Also it does not preclude charterers to pay hire and then sue for damages suffered by them due to 8 days delay causing them loss. But that is not same thing as off hire.

Fitness for the purpose

If a Charter Party specifies the Cargo a ship is required to carry under the contract, there is an undertaking by the owner that the ship is fit and suitable to carry that cargo. A ridiculous example maybe if a vessel was chartered to carry oil and owners delivered a dry cargo vessel!

Case 8

M. V. SINGAPORE CLIPPER – KARACHI

Vessel was arrested at Karachi for bringing in 12600 M. T of contaminated Malaysian palm oil, and charged with making false declarations. Charter party specified cargo of edible oil. Under International Rules a ship, which has carried petroleum fuels, must make at least three trips with non-petroleum cargo before carrying edible oil. Owners did not inform shippers that ship carried aviation gas before.

Edible Oil was loaded at Pasir Gudang. Ship’s tanks were found contaminated with lead from aviation gas. It was possible that surveyors in Singapore did not check the tanks. Burden of proof that Shipowner exercised due diligence to make his ship cargo worthy is on owner. He relies on skill and judgement of master. Captain had stated that he got the ship’s tanks cleaned under his personal supervision but did not disclose that she carried aviation fuel before!

Master could not know terms of the sub-CIP if they were not furnished to him. But he knew or ought to know rules applicable to carriage of edible oil, and consignments of cargoes his ship carried over last three voyages. Contractually he is not obliged to inform shippers unless asked. But his ship must be fit for the purpose since C/P was signed to carry a specific cargo.

Arrived ship

Depending on wording of C/P, for time on hire to start running, Charterers are entitled to have the ship arrive at the designated place for Notice of Readiness (NOR) to become effective. Test of whether she has arrived, is “whether she is within the port, dock or berth named in C/P in the sense of being in an area or within a range of proximity within reasonable contemplation.” A valid NOR can be served only if she is an arrived ship, ready to receive or discharge cargo. Whatever prevents her to arrive there is not charterers concern. Also, NOR can only be tendered at a time stipulated and only when received by proper person as per C/P.

Obviously, if charter party stipulates that vessel is to be delivered after arrival at a named port, NOR can’t be effective unless she has reached within commercial area or Port limits. If the vessel is not physically within the designated area, she is not an “Arrived Ship”, even if Master has been allotted an anchorage by port authority, unless it is so stipulated in C/P. As a general rule owners and Charterers avoid such problems by stipulating realistic conditions for ‘NOR’ to be tendered. In some charters vessel is deemed to have been delivered or redelivered at sea e.g. crossing Gibralter, or “Passing Dondra Head.” Etc. Neither in congested ports C/P may provide for NOR to be tendered when vessel has anchored as per port instructions etc.

Case 9

The Kyzikos 1989 Vessel anchored off Houston at 0645 On Dec 17 1984, with cargo of steel from Italy. Master gave NOR. Her berth was vacant but she could not berth till Dec 20. Question was if waiting time at anchorage due to fog which closed the Pilot station, should count.

Held by House of Lords, Lord Brandon.

“I am of the opinion, having regard to authorities to which I referred earlier and the context in which acronym 1144BON” is to be found in charterparty here concerned, that the phrase ‘whether in berth or not’ should be interpreted as applying only to cases where a berth is not available and not also to cases where a berth is available but is unreachable due to bad weather”.

This appeal was allowed in favour of charterers. Simple reason was that reachable on arrival means precisely what it says. Safe berth has to be ready on arrival. But if ship can’t berth because there is no pilotage due to fog, she is not on charterer’s account. Here a parallel has been drawn with the ship getting delayed due to bad weather at sea.

Case 10

The ‘Agamemnon’ was chartered for a voyage from Baton Rouge to Brisbane. Master did not give NOR at South West Pass which customary anchorage for vessels waiting to enter Mississippi river. But Baton Rouge has its own anchorage, about 170 miles upriver. Court of Appeal held that NOR given before she arrived at Baton Rouge anchorage was not valid and subsequent arrival of the vessel at Berth at Baton Rouge did not validate the NOR.

Court of Appeal has also held that NOR which is tendered at a non-contractual TIME by an arrived ship ready to load or discharge in all respects, is valid. But it will become effective to trigger commencement of lay time at the moment it could have been contractually tendered.

In Time C/P, when ‘Master to be under charterers orders as regards employment’, choice of route concerns ’employment’ of the vessel not ‘navigation’ and obliges the Master not simply to proceed but to proceed with the ‘utmost despatch.’

Case 11

In 1994, Master of ‘Hill Harmony’ refused to sail on Gt. Circle and took the rhumb line course on two voyages from Vancouver to Japan. He gave no good safety reason for this, except to say that he had encountered bad weather on a previous voyage in October and would find better weather on the longer more southerly rhumb line course. Owners agreed that vessel was designed to sail through heavy weather but claimed that choice of route was Master’s prerogative.

It was argued that since time is money in Time Charter, order to take the shorter route was an order as to employment, to achieve the utmost despatch. Between March 1 and May 31 1994, 360 ships sailed on great circle track through North Pacific Ocean without mishap and as per professional weather routing advice. This raised important issues as to where to draw the line between sailing instructions by charterers and prerogative of the Master to chose his course to navigate the ship. Arbitrators held that charterers were entitled to be compensated for time lost due to decision of Master to sail the rhumb line track. Justice Clarke in commercial Court held in favour of owners and said that Master’s decision relating to navigation took precedence.

UK Court of Appeal agreed with the commercial court and held that choice of an appropriate route was a decision about navigation and not about her employment. They added that there is difference in an order to proceed by a generally recognised route. But charterer order to sail a definite route disrupts Master’s prerogative.

House of Lords unanimously reinstated the Arbitrators award. They agreed that time being money in T/C, in absence of some overriding factor such as a real threat to safety; choice of ocean route was a matter of employment to achieve maximum earning capacity of the vessel. The Law Lords distinguished Master’s obligation to charterers and his responsibility for safety of ship, crew and cargo and said that in extreme cases Master is under an obligation NOT to obey such an order. But in this case Master gave no safety reasons for not obeying the charterer’s orders. Decision to avoid FORECAST bad weather is a navigation matter based on bonafide judgement for safety considerations.

Obligations of the master to the charterer

Obligation to operate as per charterer’s orders does not displace Master’s overriding duty to navigate the ship safely, based on his judgement and experience. Therefore Master should read and check such a C/P clause with owners and P & I club carefully. If he thinks that a route he is being asked to take is not safe at that time of the year,.and has sufficient grounds through experience and available information including weather forecasts, to believe that it is unsafe, to navigate a particular route, he should refuse the order.

Even if he feels forced to accept the order, he should lodge strong protest with owners and charterers on grounds of safety of life. Chances are that no commercial interests would take the risk of sending a Master on a route across the ocean, about the safety of which he has expressed his reservations supported by available facts

Awesome post! Keep up the great work! 🙂