Safe practices in navigation are an important aspect of the overall safety of the ship. Perhaps more important than knowing the theory of navigation. Safe Practices are followed because of good planning and commitment by the ships leadership. In the case studies given below it shall be observed that experienced watch keepers and masters involve the ships under their charge in accidents only because they failed to follow the established practices and the well defined Colregs. On studying them you may observe that each one of us is some time or the other guilty of similar lapses. Experience. no doubt, comes from developing your own knowledge and skills but it also gained when learning from other peoples mistakes. You shall agree that no one can afford to learn by making mistakes!

Bridge Team Management

Today’s ships are very much larger, they carry more cargo, more oil, more passengers, yet their crews are smaller and often of mixed nationalities. These bigger ships are operated in an ever increasingly hostile environment. One barrel of oil spilt in some pads of the world may cost one million dollars to clean up; an injured seaman will expect large settlement to reflect disablement, pain. suffering and traumatic stress disorder. Twenty years ago, collisions and groundings occurred as they do today invariably because of human error. The important difference between today’s and yesterday’s operator is the belief that claims caused by human error are avoidable, the underlying causes are understood and procedures have been set up to prevent the error occurring.

Experience shows that most navigation errors are the result of lack of bridge team management.

There are numerous examples, which illustrate these points:

- Two VLCCs from the same company, navigating at night on reciprocal courses, collided. Each ship had detected the other on their radar, but neither navigator plotted the other ship’s approach.

- On his first trip as a Master, the ship grounded off Tasmania after the master fated to make sufficient allowance for wind and tide.

There was no passage plan between the anchorage and the pilot station, or between the pilot station and the berth. The pilot had ordered full ahead four minutes after stepping on the bridge of a large ship. Although a pilot card had been exchanged, the master had no idea of the mute, which the pilot intended to follow?

- A passenger ship ran on to the rocks after the pilot missed an alter course position. The bridge team including the Master, who was on the bridge failed to notice and correct the same

There have been many different reviews of accidents. Most conclude that human failure rather than equipment failure is responsible for almost every collision, grounding or dock damage. The P&I clubs have identified following failure, recurring time and time again. For example:

- Failure to use the radar properly and to plot the approach of the approaching ships;

- Failure to abide by the Collision Regulations, to proceed at safe speed and to maintain a proper lookout;

- Failure to brief the pilot on the ship’s manoeuvring characteristics and to discuss the pilot’s intended route before handing over control, and thereafter to monitor the pilot during the passage;

- Failure to use sufficient tugs or has the ship under the control of tugs.

All of these causes involve an error of judgement, failure to communicate or simply lack of knowledge, all of which can be corrected effectively through bridge resource management.

The purpose of bridge team management, or bridge resource management is to setup a working system, which prevents these typical failures developing into an accident.

Typically, the underlying requirements of a bridge team are:

1. Every member of the team must understand:

- His responsibilities and duties,

- The responsibilities and duties of the other team members and how these alter with changes in circumstances,

- The master’s standing orders and

- A clear understanding that assistance should be called for whenever in doubt.

2. To establish formal communication channels between each member of the team. particularly with the master and especially during manoeuvres.

3. To set out formal procedures for the conduct of a navigation watch. particularly in restricted visibility or confined waters.

4. To develop passage planning and procedures for pilot supervision,

5. To develop a safety culture within the team and give guidance in dealing with commercial pressures.

A bridge team is quite small, although its size can vary. Furthermore. every member of the team will not be on duty at the same time. Most ships operate a three-watch system, which means the bridge team is divided into three separate groups or watches. The ship’s master is the leader of the team. while the 00W is the senior member of each group, although the master can join the group and take over as the senior member.

The role of the 00W changes when this happens… A watch may comprise six persons (master, 00W, quartermaster, lookout, stand-by and the pilot), or it can be a sole watch keeper. Each member of the group has a high level of individual responsibility, as it is impossible for the 00W to constantly supervise every member of the team and perform his own duties. He has to rely on members of the team alerting him to potential problems. Each member of the bridge team needs to understand precisely what is expected of him and the information, which the 00W needs to know.

Many ships are crewed with a mixture of people of different nationalities, whose first language will not be English. These people may lack confidence when in the master’s presence and not always understand instructions, which are given in English. resulting in confusion and errors. If this occurs, a time bomb is waiting to explode, which needs to be defused.

Master’s responsibility

The master is the guiding hand. It is his job to mould the team and to develop it. He will use the company’s bridge operating procedures and his own watch keeping instructions for guidance. He will need to hold frequent meetings of the entire bridge tearn to discuss both his and the company’s requirements. He should encourage open exchange of ideas between each group and be on the lookout for Possible personality clashes. He should arrange departure and arrival meetings, which will involve a detailed discussion of the passage plan. Every member of the team will need to be familiar with this. It is the master’s responsibility to encourage radar watch keeping and to instruct junior officers in ship handling. He will need to implement procedures for handing over the watch and set out clear instructions for when the 00W is to call for assistance.

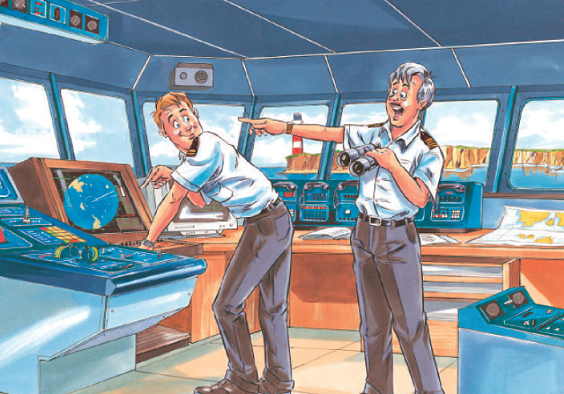

Bridge management with pilot on board

Pilots present special problems. They are temporary but full members of the bridge team are involved when the chance of contact damages with docks or berths and grounding is highest. It is the job of the master and the bridge team understand the pilots passage plan and to supervise the pilot.

The master will be able to closely supervise the pilotage operation if the passage has been planned from berth to berth and the plan for port entry discussed with the pilot. The master shall then be in a better position to anticipate rather than react to the situation when the plan fails and be able to take control before there is an emergency, rather than merely react at crisis point.

The use of tugs should always be discussed with the pilot before committing the vessel to the proposed manoeuvre. Even ships, which are highly manoeuvrable, may require tug assistance due to the prevailing weather or tidal conditions. From its experience with dock damage claims, the Club believes that when large ships are navigating in restricted waters, they should always be under the control of tugs.

Shipboard familiarisation training is very important, officers need to have confidence in the equipment they use and have experience in ship handling. Familiarisation training is an essential part of bridge team management. Team working will expose weaknesses so that training can be tailored to suit the needs of the Individual.

Team skills may not come naturally to some people, while the busy work environment on most ships may mean the development of team skills is neglected. Many owners have recognised this and sent their masters, officers and in some cases, the entire bridge team on a bridge team management course.

These courses use sophisticated bridge simulation techniques to model a ship’s bridge and set up realistic examples of port arrival. departure and coastal navigation. A team can be put through a number of exercises, each of which will highlight a particular team skill.

Often the exercises are videoed so that mistakes can be displayed and discussed. Bridge team management courses offer the opportunity to practice tearns kill without putting a ship and its cargo or the environment at risk, skills which can be taken back to the ship and applied.

They improve awareness of the ship’s and the operator’s limitations and demonstrate how easily a small error can lead to a large accident. Bridge team management courses may not eliminate claims. which are caused by human error, but they will eliminate communication problems and improve significantly skills in ship handling.

These courses are now recommended to all officers.

Error in Navigation – Passage Planning

A container ship ran aground on a reef near the approach to the Singapore Strait. At first sight the owner should have been entitled to the defence of negligence in navigation under The Hague Visby Rules. The ship’s officers had preplanned the ship’s course as a formal passage plan. This course was one that took the ship only two miles to the east of the reef in an area where tidal currents were known to be variable. A navigator should have known that this distance was too close to the reef, which should have been passed at a considerably greater distance. The cargo owners alleged that the ship had left her loading port with an inherently unsafe passage plan and was therefore unseaworthy at the commencement of the voyage. There was considerable doubt as to whether such an argument would succeed, it was clear, at least after the event, that a course only two miles off the reef was unsafe. The weakness of the case was that they did not have in place any regular system for checking the quality of the navigation of has senior officers. Few companies do. However, it must be accepted now that owners do have a duty to check in some way the competence in navigation of their officers. It was recommend that:

- Each ship should receive an annual safety audit in any event

- As part of the audit a random selection from the previous year’s passage plans should be checked against the charts in use.

- If any evidence of imprudent navigation is found the officers involved should be earned and corrected

Bridge – Who is in control?

A large claim resulted from a small tanker colliding with a navigation mark. after the officer on watch failed to alter course. He believed the master has taken over the watch. Previously, the master had instructed the officer on watch about a sharp alteration of course. which was required so that the ship could enter the mouth of the Detroit River. The course alteration had to be made immediately the ship had a particular light buoy at 45 degrees on the starboard bow. The master. after giving the instructions, went below, but shortly before the ship arrived at the alter course position he returned to the bridge.

The officer of the watch thought that the master had taken back control after returning to the bridge and neither gave the instruction to the helmsman to alter course nor checked whether the master had altered the course as decided. The ship hit a navigation light.

Bridge procedures should require that the master formally instruct the officer on watch that he is taking over the watch; otherwise, the officer should always keep the control of the watch.

Simple words As “Second mate I have taken over or just “take over please’. can remove this anomaly.

Chart Corrections

A ship grounded and became a wreck because she did.not have the correct chart. The Club may have to pay $1.5 million. A ship must maintain a proper system for the supply and correction of charts. In order to maintain such a system ensure that:

- A list of each and every chart is on board;

- Supply of weekly notices to mariners’ on a regular basis by appropriate means are obtained;

- A chart correction log is maintained:

- Required chart are actually on board and are maintained up-to-date.

- Positive reporting arrangement in this respect is maintained from the ship to management.

In the past shipowners may have generally left it to their masters to make sure that charts are updated. However, the English House of Lords has held in the case of the MARION (1984) that shipowners must ensure that their ships are supplied with up-to-date charts and that chart corrections are made. It is not sufficient for the owners to rely on their masters to obtain the necessary navigation publications and information. It may also be noted that masters are also being prosecuted and ships detained for not maintaining charts on board up-to-date.

Passage Planning and Pilotage

Some masters consider it pointless to plan a river passage. There is a pilot on board to navigate the ship and anyway it is impossible to predict the effects of wind and current. Often a river chart may not be detailed enough or its scale may be too small to allow a detailed plan for the passage of an unfamiliar river. Their passage plans start and end at the pilot station. However, after investigating many dock damage and grounding claims, the P&I club Managers are firmly of the opinion that passage planning is necessary berth to berth. The Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) recently reached the same conclusion when they investigated the grounding of the Iron Baron at the entrance to the River Tamar in Tasmania.

The Iron Baron had anchored in the river waiting for a pilot and had then weighed anchor and proceeded to the pilot station. There was a strong northerly wind and a flood tide. The master, who was navigating the ship, was monitoring her position on the radar. Without realising it, the master allowed the ship to overshoot the pilot’s boarding position by more than one mile and, by the time the pilot had boarded, the ship was already dangerously close to the eastern end of the reef, where she eventually grounded. The master had not made sufficient allowance for the wind and tide and was not aware that the ship was more than a mile south of the pilot’s boarding position. He had not been monitoring the ship’s progress with a position on a chart. Had this been done, then he would have realised the ship was off its course and being set to the south.

In their report AMSA concluded that:

‘A full passage plan, detailing safe clearing distances and bearings to be used while picking up the pilot, had not been prepared and proper management of the bridge resources had not been considered.’

The Sea Empress grounding and spill of 70,000 tons of crude oil gives a similar lesson. The preliminary report of the UK Marine Accident Investigation Branch states that to ship picked up pilot at 1940 hours and he ordered full ahead towards the entrance channel at 1944 hours. So she first grounded at 20.07. Four minutes cannot possibly be enough time for a British pilot and a Russian master to discuss a difficult approach of a large ship through a narrow channel. The interim report states that the master and the pilot had not discussed and agreed a plan for the approach. This is just the point the clubs have learnt from a host of far less serious claims.

A recent Club case involved a bulk carrier grounding in shallow water because of squat. This ship was travelling too fast and squat caused the bow to touch bottom and resulted in loss of steerage. The ship veered out of the channel and grounded. A small reduction in speed gives a large reduction in squat. A passage plan in shallow water would indicate the maximum permitted speed so that the effects of squat are minimised.

A simple passage plan is nothing more than a course on a chart telling the navigator which way to steer, but a plan for coastal or river transits are more detailed. Regardless of the type of passage, every plan should show:

- The intended track (line on the chart),

- Areas to avoid for safety reasons,

- Areas of shallow water, other hazards to navigation,

- Wrecks,

- Course changes and

- The next chart position.

Plans for river passages or passages in narrow channels should also include:

- Tidal information,

- Speed restrictions,

- Position to change course,

- Alternative routes in emergencies,

- Parallel index lines

- Emphasis on leading marks and

- Highlight sharp or difficult bends and areas of cross currents.

All this information should be marked on the chart in use. Care needs to be taken to avoid cluttering the chart with pencil marks with only the most important information or the most dangerous hazards being shown.

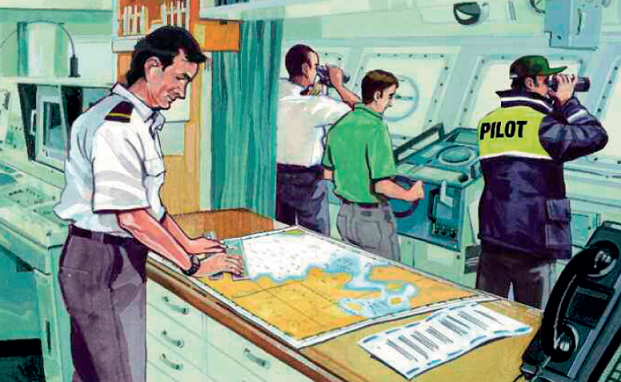

Once the passage has been planned its contents can be circulated to the bridge team and a copy given to the pilot when he boards. While passage planning, it is necessary to ensure that checklists and procedures are understood and followed.

Execution and monitoring of a passage is as important as planning it and each member of the bridge team will need to know his responsibilities and duties during pilotage, For example:

- Who will track the ship’s position?

- Who will plot approaching ships on the radar?

- Who will deal with VHF calls?

- When should the master be called? This is Particularly important for long River or coastal passages when it may not be either practical or desirable to have the master continuously on the bridge. Passage planning is not difficult but it will require increased effort and discipline by the bridge team.

However. there is more to passage planning than looking at a chart and Pre-planning the passage. The plan has to be executed and monitored. Experience has shown that if the passage has not been planned, then the probability of an accident will increase. Regrettably, this appears to be exactly what is happening.

The number of high profile grounding incidents is startling and these can be prevented if the officers plan the voyage from pilot station to berth as carefully as the rest of the voyage.

Passage planning

The consequences of a failure to plan a passage properly and to ensure that the plan is effectively executed are graphically illustrated by the stranding and subsequent total loss of a container ship, resulting in significant cargo claims.

The ship, modern and well equipped, was approaching the pilot station at Sao Francisco do Sul, Brazil. The approach was via a narrow channel six cables wide, delineated by islands to the north and south, the island to the north being marked by a light with a range of 26 miles. No passage plan had been drawn up and the chart was not annotated with any of the prescribed advice. Weather conditions were fair, the visibility generally good, but occasionally reduced by rain showers.

The master, third officer and helmsman manned the bridge. The master was unfamiliar with the port, but did not attend the bridge and take over the con until the ship was on the final approach course, 5 miles from the entrance. The ship was 3 cables to starboard of the intended track and heading directly for the islands bounding the north side of the channel, but no action was taken at this stage to regain the intended track. Position fixing was effected using it single radar range and bearing at 10-minute intervals. No use was made of parallel indexing, which would have provided a continuous assessment of deviation from the intended track.

An alteration of course of 30° to port was made to regain the intended track, with the islands on the north side of the channel dead ahead at a range of 2 miles. This had no discernible effect and some 10 minutes later with the ship just a mile from the island, a further 20° alteration of course to port was made. The helmsman was despatched to assist with rigging the pilot ladder, necessitating the third officer taking the helm and leaving the master unsupported to both navigate and control the ship. This further alteration of course to port again proved ineffectual and. some 10 minutes later, the ship grounded with the main engine still turning ahead. The master had continued to monitor the radar in an attempt to determine his position, without initiating any positive action, until the ship grounded. At any time prior to the grounding, the incident could have been avoided by putting the engine astern

Efforts to refloat the ship failed and she was declared a constructive total loss shortly thereafter.

Three separate enquiries into this incident have been held by the local port authority, the Brazilian authorities and in Germany, as the issuing authority for the master’s certificate, respectively. Whilst the Brazilian authorities’ enquiry has yet to report, the other two have concluded that the grounding was solely attributable to negligent navigation.

The stranding and subsequent total loss of this ship was entirely due to negligent navigation arising from a failure to devise, agree and implement an effective passage plan for the approach. In light of the catastrophic consequences of the failure to do so in this instance, masers are reminded to ensure that passage planning and execution are accorded the appropriate importance on their ships.

The Master/Pilot

Recent statistics from Dot Norske Veritas Indicate that 98% of all marine casualties occur in restricted waters, 60% of them involving ships with a pilot embarked.

This is not altogether surprising. Ships in restricted waters are invariably constrained to operating in closer proximity to other vessels and hazards than in the normal seagoing environment, thereby placing them at greater risk. Nevertheless, the consistently high incidence of casualties, which occur with a pilot embarked, is a major source of concern.

In theory, at least, the greater exposure to hazards in pilotage areas should be adequately compensated by the addition to the bridge team of a pilot, employed for his expert knowledge of local conditions. This expertise, combined with the knowledge and experience of the master with respect to the handling characteristics of his ship and the assistance of the bridge team. should be sufficient to assure the safety of the vessel under all but the most unpredictable of circumstances. Regrettably, casualty statistics consistently prove this not to be the case in practice.

In a somewhat subjective judgement, many in the marine industry attribute this to pilot error, evidently believing that the training and competence of pilots has plumbed hitherto unprecedented depths. as witness a recent description of pilots as “dangerous additions to the crew.” However, the Managers do not accept that many of these casualties are solely attributable to errors of commission or omission by the pilot. Rather, it is contended that they are generally the consequence of a failure by the pilot, the master and his bridge team to form an effective working relationship and to function as a cohesive team in a manner conducive to the safe navigation of the vessel. An objective review of accidents attributed to pilot error will, all too often, reveal a degree of contributory culpability on the part of the master, or a member of his bridge team, ranging from complacency to outright dereliction of duty.

The grounding of the Sea Empress illustrates the problem very clearly. The ship grounded in the entrance to Milford Haven in February 1996, spilling 72,000 tons of crude oil, when a crosscurrent set the vessel down on to rocks during the approach. A pilot was embarked. The report by the UK’s Marine Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB) concluded that the immediate cause of the grounding was pilot error, in that he failed to take appropriate and effective action to keep the vessel in the deepest part of the channel. The report further concluded that although the ship had prepared a passage plan for the pilotage, the pilot and master had not discussed and agreed the plan. Therefore, neither the master nor the chief officer knew what the pilot’s intentions were. The report made it quite clear that the failure to agree a passage plan precluded the master from being able to monitor the approach effectively and concluded that, had the master’s plan been followed, the grounding may have been avoided.

Also embodied in the MAIB report are two statements, which are of particular significance, namely:

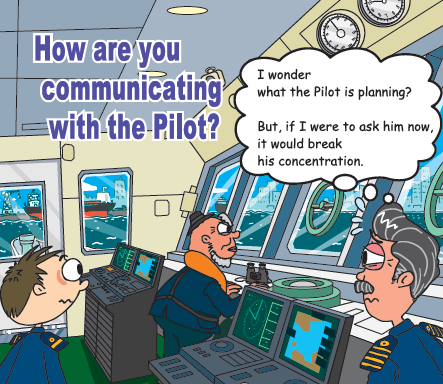

(a) Pilots at Milford Haven did not normally advise masters of their intentions with respect to routing when entering the port. This situation is not considered unique to Milford Haven.

(b) Many masters, not just at Milford Haven, share a similar attitude, saying in effect “she’s all yours, pilot”

The Managers are in no doubt that the conclusions of the MAIB report, together with the statements outlined above, typify many such incidents and are the fundamental cause of the unacceptably high incidence of casualties, which occur with a pilot embarked. In essence, the pilot is frequently unwilling to discuss his plan with the master and the master makes little or no effort to ascertain the pilot’s intentions, or to monitor or assist him by plotting the ship’s position at intervals appropriate to the passage being undertaken, thereby effectively handing the responsibility for the ship to the pilot. There can be no parallel in the transport industry, or any other walk of life, where a person will effectively hand the responsibility vested in his foss multi-million dollar asset to a complete stranger whose competence he has had no opportunity to assess. This appalling situation is often compounded by the fact that no effort is made to ascertain how the pilot intends to discharge the task with which he is being entrusted and that little or no to monitor the ship’s progress thereafter. This is a recipe for disaster and it hardly surprising that disaster Is often the outcome.

There can be no doubt that the establishment of an effective working relationship between master and pilot, enabling the latter to function effectively as an integral part of the bridge team whilst he has the con, is vital to the elimination in pilotage waters.

The requirements fundamental to the establishment of an effective working relationship are encapsulated in the Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for seafarers, the STCW Code, and are reproduced below for ease of reference:

Navigation with pilot on board

Despite the duties and obligations of pilots, their presence on board does not relieve the master or officer in charge of the navigational watch from their duties and obligations for the safety of the ship. The master and the pilot shall exchange information regarding navigation procedures, local conditions and the ship’s characteristics. The master and/or the officer in charge of the navigational watch shall co-operate closely with the pilot and maintain an accurate check on the ship’s position and movement.

If in any doubt as to the pilot’s actions or intentions, the officer in charge of the navigational watch shall seek clarification from the pilot and, if doubt still exists, shall notify the master immediately and take whatever action is necessary before the master arrives.

The requirement for the master to be fully cognisant of and in agreement with the pilots intentions with respect to the planned route, speeds, deployment of tugs and contingency plans before permitting the ship to proceed is crucial. Failure to comply will preclude effective supervision and monitoring of the pilot. It may also render the master powerless to intervene should deviation from the plan occur, either deliberately or inadvertently, possibly exposing the ship to unnecessary risk. and is itself an abdication of the master’s responsibilities. It is also imperative that all members of the bridge learn understand the plan. Without this, the officer on watch (00W) may feel that he has been excluded from events and adopt the role of disinterested spectator, in tum leaving the pilot feeling isolated and unsupported. which will do little to foster harmonious and effective relations.

The importance of these provisions was further underlined by the grounding of the Peacock when under pilotage in the environmentally sensitive area of the Great Barrier Reef . The report by the Australian authorities concluded that the grounding occurred when the pilot lost situational awareness and missed an alteration of course. The balance of probability being that he fell asleep.

A significant contributory factor to the incident was that there had been no dialogue at all between pilot and the 00W due to the latter’s limited command of English. The pilot had not pointed out the alteration of course and the 00W had not been fixing the vessel’s position at regular intervals. Therefore, when the pilot lost situational awareness, the 00W was not sufficiently acquainted with either the plan or the situation to intervene and the vessel struck a reef at full speed.

Masters frequently complain that discussing and agreeing a plan with the pilot for port arrival or departure is difficult, either due to the lack of time available to do so. or because the pilot is unwilling to enter into such a discussion. With regard to the timescale, a productive discussion between willing parties need only take a few minutes.

Whilst recognising that the operating costs of modern ships are high and that time is invariably of the essence, it is fundamental to safe navigation that the bridge team understand the pilot’s intentions. Consideration should therefore be given to delaying the intended manoeuvre to allow this discussion to take place, provided always that such a delay, of itself, does not place the vessel at risk.

The difficulties of holding an objective discussion with an unwilling pilot are acknowledged. Nevertheless, masters are urged to insist that a discussion of the passage plan does take place because, without it, the prospects of retaining effective command of the vessel when under pilotage are considerably reduced.

The MAIB report into the Sea Empress grounding recommends that the pilots at Milford Haven be instructed to discuss and agree a plan with the master prior to commencing any manoeuvre and it is hoped that pilotage authorities on local, national and international levels will take this recommendation on board and apply it to their respective areas of authority.

Help for the master may also be forthcoming from the STCW Code. Time constraints prevented the inclusion of provisions on the training and certification of pilots in STCW 95, but the STCW Conference passed a resolution recommending that such provisions should be developed. Should this recommendation be enacted, any provisions would clearly mirror the requirements currently pertaining to masters.

It is recognised by the Managers that development of an effective working relationship between the pilot and the master and his bridge team is not a panacea. Nevertheless, it is believed that the will to do so, combined with a modicum of effort from masters and pilots, will result in a significant reduction in the incidence of casualties, which occur with a pilot embarked.