ANCHOR WORK

Explain the various terminologies used in anchoring.

- Windrode: used to describe a vessel when she is riding head to wind.

- Tiderode: used to describe a vessel when she is riding head to tide.

- Lee Tide: A tidal stream which is setting to leeward or downwind. The water surface has a minimum of chop on it, but the combined forces of wind and tide are acting upon the ship.

- Weather tide: A tidal stream which is setting to windward or upwind. The water surface is very choppy, but the forces of wind and tide are acting in opposite direction on the ship.

- Shortening-in: The cable is shortened-in when some of it is hove inboard.

- Growing: The way the cable is leading from the hawse pipe, e.g. a cable is growing aft when it leads aft.

- Short stay: A cable is at short stay when it is taut and leading down to the water close to the vertical.

- Long stay: A cable is at long stay when it is taut and leading down to the water close to the horizontal.

- Up and down: The cable is up-and-down when it is leading vertically to the water.

- Come to, brought up, got her cable: These are used when a vessel is riding to her anchor and cable, and the former is holding.

- Snub cable: To stop the cable running out by using the brake on the windlass.

- Range cable: To lay the cable on deck, or a wharf, or in a dry-dock, etc.

- Veer cable, Walk back: To pay out cable under power, i.e. using the windlass motor.

- Surge cable: To allow cable to run out freely, not using brake or windlass power.

- Render cable: The cable is rendered when the brake is applied slackly, so that as weight comes on the cable it is able to run out slowly.

- A’cockbill: used to describe the anchor when it has been lowered and clear of the hawse pipe and is hanging vertically.

- Foul anchor: An anchor which is caught in an underwater cable, or which has brought old hawsers to the surface with it, or which is fouled by its own cable.

- Foul hawse: When both anchors are out and the cables are entwined or crossed.

- Clear hawse: When both anchors are out and the cables are clear of one another.

- Open hawse: When both anchors are out and the cables lead broad out on their own bows.

- Nipped cable: The cable is nipped when an obstruction, such as the stem or hawse pipe up, causes it to change direction sharply.

Explain in detail the procedure for anchoring.

Following is the procedure of anchoring:

- Scope of cable: The ‘scope’ of the cable is the ratio of the length of cable paid out to

the depth of water. Amount of cable to use depends upon the following:

• Nature of holding ground (Stiff clay, rock, shells & stones – poor holding ground)

• Amount of swing-room available as the wind or stream changes direction.

• The degree of exposure to bad weather at the anchorage.

• The strength of the wind or stream at the anchorage.

• The duration of stay at anchor.

• The type of anchor and cable. - Planning: The anchor plan must be made and discussed in advance with the anchor party. This is usually done during the pre-arrival bridge team meeting. Planning must include deciding the anchorage position, planning of the approach, plan for turning the vessel, back-up anchorage spot, contingency planning, ascertaining the weather and tidal conditions, etc. Reference must be made to the information given in ASD, Guide to Port entry, Local agent’s message, weather forecasts, past experience of Officers, etc. Planning must be flexible to be amended at a later stage if required.

- Clearing Anchors: Anchors must be cleared away and prepared well in advance. This includes removing hawse pipe covers, removing of the lashings, removing spurling pipe covers/cement, checking windlass brakes are fully tight, ensuring bow stopper in place, etc.

- Approach: The anchorage must be approached at slow speed paying careful attention to the nearby vessels, some of which may be leaving the anchorage or preparing for anchoring. Any required reporting must be carried out. All pre-arrival checks such as engines, steering gear, etc. must be carried out well before reaching the anchorage.

- Letting Go: Anchor must be lowered to water level depending upon the depth of water and kept ready for letting go. Upon reaching the anchorage spot, orders must be clearly given to let go the anchor. Anchor must be let go when the ship is stopped and preferably engines must be kept on dead slow astern as the anchor is let go. Engines must be used to relieve the stresses in the cable just before the vessel brings-to. Engines must be stopped almost immediately when the vessel drifts astern laying out her cable which grows continually ahead.

- Allow the cable to run freely and check it on the brake when the required number of shackles are out. Sometimes with the weight of the anchor off the cable, the cable does not release even when the brake is open. When the weight comes on the cable as vessel moves aft the cable will render. In deeper waters, anchor should be walked back to within 4-5m from the sea bed and let go from there. Thereafter, the brakes should be fully tightened and bow stopper must be put in place.

How will you anchor at Chittagong anchoring?

The Chittagong anchorage is very congested with vessels arriving at the anchorage for lighterage operations before entering the river. Entering the river and anchoring at Chittagong is challenging due to strong currents especially during the monsoon season (June to November) when the weather conditions can deteriorate with little or no advance warning. I will do the following when anchoring at Chittagong anchorage:

- I will do the planning carefully considering weather conditions, strength and direction of the current, tidal changes, traffic in the vicinity, etc.

- While approaching Chittagong Road, I will not attempt to cross bow of vessels at anchor/underway to avoid a collision due to the prevailing strong current. If it is inevitable to cross, I will do so giving wide berth to those vessels.

- I will carefully study the anchorage area and local conditions such as wind, tides and currents.

- I will stem the tide while anchoring and use bold engine movements to maintain vessel’s position. I will let go more number of shackles than normal. It is recommended to pay out at least nine shackles on deck or more depending on draft and UKC.

- I will keep sufficient distance from other vessels considering the vessel’s swinging circle and the time it will take before making contact with another vessel should my vessel drag anchor.

- I will keep sufficient distance from shoals and other obstructions to have more time in hand in case the vessel starts to drag anchor.

- I will instruct the OOW’s to monitor vessel’s position and distance from other vessels more frequently and inform me immediately in case any sign of anchor dragging is observed.

- I will have the main engines ready at all times.

- I will instruct the OOW’s to use the main engines if required to reduce the stress on the cable.

- One crew member will be stationed forward to ensure no excessive load on the cable or windlass.

How will you go about anchoring in Indian waters in the SW monsoon season?

The period June to September is referred to as the ‘Southwest Monsoon’ period. During this period, the weather is rough and this makes anchoring even more challenging and critical. I will do the following:

- I will pay more shackles than normal considering the depth of the water, weather and various other factors.

- I will approach the anchorage heading upwind as I can control my ship easily and will have little leeway.

- I will make bold use of engines to relieve stresses on the cable and maintain ship’s

position while anchoring. - I will ensure my engines are always ready while at anchor or on a 5 min notice.

- I will keep one crew member forward to monitor the cable lead and stresses.

- I will instruct OOW’s to keep a strict anchor watch.

- If the weather is very rough, I will abort and consider drifting in safer waters. I will also refer to Company SMS requirements in this regard.

How will you anchor in deep waters such as Fujairah? What precautions will you take?

• I will comply with Company SMS which will specify the company requirements for deep water anchorage.

• I will carefully calculate the length of cable to be used considering the depth, heaving capacity of the windlass and period of stay at anchorage.

• I will pick a spot with the least depth considering other factors such as distance from other vessels at anchor, anchorage limits, etc.

• I will carry out the entire operation of anchoring under power. i.e. walk back fully. I will not take the gypsy out of gear at all, because the heavy weight of the cable between sea-bed and hawse pipe will undoubtedly take charge.

• I will ensure the vessel’s SOG is zero while walking back. This is to avoid any excessive load / damage to the windlass. After laying 1 to 2 shackles on the sea bed, I will use short burst of engine power, no more than dead slow ahead or astern to range the cable to the required length.

• I will ensure that the windlass brake linings are in a good condition and sufficient power is available on deck for the windlass.

Why do we use more number of cables in heavy weather?

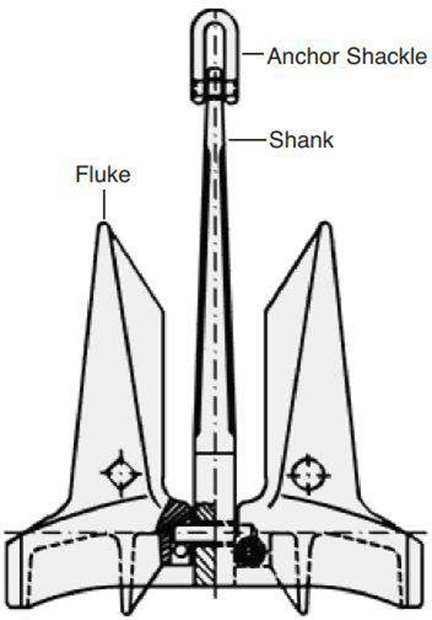

An anchor provides maximum holding power when its flukes are embedded in the sea bed. This occurs when the anchor shank lies on the sea bed and the anchor cable pulls horizontally at the anchor shackle. When the pull increases, the cable lying on the sea bed is lifted off, creating a larger angle above the horizontal. As the angle increases, the holding power reduces. As a guide, a pull of 5 degrees above the horizontal reduces the holding power by 25% and a pull of 15 degrees reduces the holding power by 50%. Therefore, to maximize the holding power, the scope of the cable should be sufficient to ensure that, in fair weather, an adequate length of cable will lie along the sea bed, allowing the cable to pull the anchor horizontally.

This is why extra cable is paid out when the wind, sea or current increases. The extra weight of the chain and the additional scope allows the shank of the anchor to lie horizontally on the seabed causing the flukes to dig in. The curve of the cable, or catenary, absorbs any shocks when riding to wind and sea. A catenary is necessary for the cable to have a horizontal pull on the anchor and ensure maximum holding power

Why do you always stem the current when approaching the anchorage?

We always stem the current when approaching the anchorage because:

- Helm is useful even when making no way over the ground due to the water running past the vessel’s rudder.

- The opposing current makes it easier to stop the vessel or maintain the desired speed for anchoring working the main engine ahead depending on the strength of the current.

- Another advantage is that the anchor chain can get laid up instead of piling up at one place only. As the vessel falls back with the current, the chain gets laid up without even having to give any astern kick.

How will a manoeuvring diagram help you before anchoring?

• It will provide information about the turning circle in the present condition (load / ballast) and in shallow waters which will be required if vessel has to swing before anchoring.

• Stopping distance details will help to ascertain the safe speed to proceed to and approach the anchorage.

Anchor is stuck while heaving and is not coming up. State your actions.

• I will slack the cable for a few metres and then pick up again.

• I will give engine kicks ahead or astern depending on the lead of the cable and bring the cable to up and down position so as to have minimum load on the windlass.

• If this does not work, I will go slightly ahead and let the cable lead aft.

• If this does not work too, I will go astern and try the same thing.

• I can try changing the heading of the vessel using B/T or helm and then try heaving.

• I will steer the vessel slowly in an arc towards the anchor and try to rotate the anchor and break it out by constant movement.

• I will check if sufficient power is available to the windlass.

• If all efforts go in vain, last option would be to slip the anchor after tying the anchor buoy for later recovery.

What is the procedure of slipping anchor? When would you choose to do this?

Slipping an anchor is an emergency procedure where by the cable is detached at its inner end and both, the anchor and the cable are cast off into the sea. It is generally intended that they are to be recovered at a subsequent time.

Slipping is always done from the bitter end only as it is unsafe to try to open one of the intermediate shackles on deck. The chain end (bitter end) is secured to a strong point in the chain locker in one of many ways. It has an arrangement that incorporates means for

emergency release, which can be released from the forepeak store without requiring any person to enter the chain locker. This is usually accessible from the forecastle store and a sledge hammer is provided for the bitter end pin to be taken out. It will be marked as ‘Bitter end release’ and whether port or stbd anchor. As the bitter end pin is removed, the chain end is no more secured to the vessel and once the brakes are released, the chain will run out fully under its own weight. The cable should be buoyed in order to effect later recovery.

Procedure is as follows:

• First, the engines are worked ahead so that the cable is up and down and bearing the minimum of stress, only its weight in fact.

• Anchor buoy is tied if time is available.

• The brakes are kept fully tight and the bitter end is disconnected from the ship using the sledge hammer provided.

• The brakes are slackened sufficiently enough for the cable to run out safely.

Slipping the anchor is mainly done when-

- It is practically impossible to heave up the anchor.

- Heaving up the anchor puts the ship in a dangerous situation, or

- The anchor is stuck to the seabed, or to prevent damage to the ship, windlass, etc.

What is foul anchor? What will you do in such cases?

Foul anchor is an anchor which is caught in an underwater cable or obstruction, or which has brought old hawsers to the surface with it, or which is fouled by its own cable.

When Fouled By Under Water Obstruction:

I will move the vessel ahead under engines, paying out cable until it grows well astern. When the vessel is brought upto with the cable growing astern and the cable is taut, I will work the engines ahead slowly and see if the cable breaks out slowly. In case it does not, then I will steer the vessel slowly in an arc towards the anchor and try to rotate the anchor and break it out by constant movement. If still unsuccessful, I will then try the above procedures using astern movements. If still not successful, then I will rig up an anchor buoy and slip cable for later recovery.

When Fouled With Wire Cable, etc:

I will heave up the anchor and the fouling well up into the hawse pipe. I will have a fiber rope passed around the obstruction and heave up both ends of the rope and make it fast on the forecastle deck. Now I will walk back the anchor until it is clear of the obstruction. The obstruction which is now clear of the anchor can be released by slipping the fiber rope. I will then heave up the anchor into the hawse pipe.

What all equipments you have onboard for anchor maintenance?

We have the following equipments onboard for anchor maintenance:

- The windlass

- Bow stopper

- Anchor lashings / Devil’s claw

- Anchor Wash

- Spare joining shackles (2) (Kenter shackles)

- Spare D-shackle (1)

- Spare Taper pin for D-shackles (1)

- Spare Taper pins for Kenter shackles (2)

- Lead plugs (6)

- Disengaging Tool for Kenter shackles

- Sledge Hammers (2)

- Chain hooks (2)

- Anchor buoy (2)

What types of anchors do you know of? Which one did you have on your last ship?

Following are the types of anchors based on their holding power as described in IACS Rules on Mooring, Anchoring and Towing:

Ordinary stockless anchors

Ordinary anchors of ‘stockless’ type are to be generally adopted and they are to be of appropriate design. The mass of the heads of stockless anchors including pins and fittings are not to be less than 60% of the total mass of the anchor. The mass, per anchor, must be in accordance with the mass given in Table 1.

High Holding Power (HHP) anchors

A ‘high holding power’ anchor is an anchor with a holding power of at least twice that of an ordinary stockless anchor of the same mass. When special type of anchors designated ‘HHP anchor’ of proven superior holding ability are used as bower anchors, the mass of each anchor may be 75% of the mass required for ordinary stockless bower anchors as given in Table 1.

Super High Holding Power (SHHP) anchors

A ‘super high holding power’ anchor is an anchor with a holding power of at least four times that of an ordinary stockless anchor of the same mass. The use of SHHP anchors is limited to restricted service ships as defined by the Society. The SHHP anchor mass is generally not to exceed 1500 kg. When SHHP anchors of the proven holding power are used as bower anchors, the mass of each such anchor may be reduced to not less than 50% of the mass required for ordinary stockless anchors given in Table 1.

Other types of anchors (based on construction) are:

- The Admiralty Pattern, Stocked or common anchors.

- The patent stockless anchors

- Admiralty Cast Type 14 Stockless anchors

- Offshore anchors

- Plough anchors

Like most merchant ships, my last ship had an Admiralty Cast Anchor Type A.C. 14 Stockless anchor. Such an anchor is proved to have great stability. In almost all types of seabed, it has a holding power of 2.5 to 3 times that of the stockless standard anchor of equal weight.

What is Admiralty Cast type 14 anchor and how is it different from the rest?

Admiralty Cast type 14 is a stockless anchor which has high holding power compared to other stockless anchors of the same weight.

They are used extensively as a bower anchors because of their excellent holding properties. With the increase in size of ships, the large tankers of today require anchors with greater holding power. The AC Type 14 developed in the UK, has the required properties.

It is different from the rest as –

• It has more than twice the holding power of a conventional stockless anchor of the same weight. With such an obvious advantage, Class grants a 25% reduction in regulation weight.

• The holding properties are directly related to the pre-fabricated construction of the fluke area, the angle of which operates up to 35° to the shank.

How and with what will you measure the anchor cable thickness?

IACS Guidance no 79 gives the following guidelines,

Joining shackles, D-shackles and other cable fittings should be gauged at their point of greatest wear down. Consideration should be given to replacement when the wear down equates to 12% loss of diameter over original.

- Anchor chain calibration

D1 = average of measured diameter (mm) =(d1 + d2) / 2

where d1 and d2 are measured diameters of the chain link in the area of maximum wear

D1 ≥ 0.88 D0 (where D0 = original diameter in mm)

- Measurements of Loose stud of anchor chain

a) Maximum lateral stud movements ≤ 0.05 Do where DO = original diameter (mm)

b) Maximum axial stud movements ≤ 0.03 Do where DO = original diameter (mm)

c) Maximum gap between Link and Stud ≤ 3mm

All the measurements of the thickness can be accurately done using Vernier calipers of appropriate size. Other measurements such as the length of the link, width, etc can also be done with a measuring tape.

What is snubbing of cable?

Snubbing of cable is to stop the cable running out by applying the brake. A vessel is said to snub round on her anchor when she checks (snubs or stops) the paying out of the cable by applying the brake on the windlass, so causing the cable to act as a spring, turning the bow smartly in the direction of the cable.

How will you calculate the swinging circle in case of anchoring?

Swinging circle is the circle in which the vessel is expected to swing when at anchor. The radius for drawing a swinging circle is calculated by adding the ship’s length and the length of the cable from the hawse pipe to the anchor. The centre of the circle will be the point where the anchor is dropped to the seabed. (Number of Shackles x 27.5 m + Length of the Ship in meters)

Note: ‘drag circle’ is a circle drawn with a radius that is found by substituting the ship’s length by the length between the bow and bridge in the above formula. Any bearing taken to check on the position of the ship should, if the anchor is holding, fall within the drag circle. If a fix falls outside the drag circle, then the anchor is dragging.

How does wind and current act on an anchored vessel?

Wind causes the vessel to have a heading upwind as the pivot point is right forward and the wind causes the vessel to swing in order to always lie upwind.

Where there are gusts, a vessel will sheer back and forth, falling off first one way and then the other. The bow is blown off until the cable is tight and then with the spring action, the bow surges back in. The load on the anchor due to the wind depends on two factors:

- Wind speed

- Exposed surface area of the wind (windage area)

Loads caused by currents may be insignificant in many protected anchorages but require consideration when anchorage areas are in river estuaries or areas subject to significant tidal currents. The effect of the current is that the vessel at anchor will always stem the current. During tidal changes, when the direction of the current changes, the vessel will swing successively in one direction and then the other.

What forces are acting on the anchor cable at anchorage?

Following are the various forces acting on the anchor cable at anchorage:

- Environmental forces acting on an anchored vessel are the forces resulting from wind, current and waves.

- Tensile forces – loads that attempt to elongate the cable in the longitudinal direction.

- Vibrational loads – due to machinery and other vessel components that have high frequencies of operation.

- Torsional forces – refers to the twisting of a structure when one end is kept fixed. This causes distortion when the individual links knotted or twisted. S

- Thermal forces – due of temperature changes that occur near the anchor.

- Chemical forces – due to the corrosion of the material due to rusting or exposure to organisms in the water.

How will you anchor your ship in Wind force 7 and 2 knots of current?

If the wind force is 7 I will prefer not to anchor and rather chose to find a suitable safe area to drift, keeping all concerned parties informed. As per my Company SMS, anchoring must be avoided if wind force is greater than BF 6. I will also check the weather forecast and take information from local agent and VTS if weather is expected to improve and accordingly make a decision. If it is just a gust of wind, I will delay the anchoring until wind speed reduces.

What is hanging off an anchor? How will you hang off an anchor?

Hanging off an anchor is the removal of the anchor out of the hawse pipe and hanging it off the ship’s side. It is done to either enable the vessel to be moored to a buoy or towed using the anchor chain through the hawse pipe.

Procedure to hang off an anchor:

- Walk back the anchor clear of the hawse pipe.

- Secure one end of the 1st easing wire on the mooring bit.

- Pass the other end through the panama lead, through the anchor crown D shackle (as a bight) and back through the Panama lead on to the warping drum of the windlass.

- Rig a preventer wire (as a bight) through the anchor crown D shackle, pass it through the fairlead well forward and secure it on the mooring bits.

- Ensure there is sufficient slack on the preventer wire.

- Slack on the anchor chain until the preventer becomes taut and the 1st easing wire is up and down and the anchor is under the shoulder. (see image on next page)

- Continue to walk back the chain until the next joining shackle is on the deck.

- Heave on the 1st easing wire and secure the anchor in the up and down position.

- Rig up the 2nd easing wire forward of the joining shackle (on a bight) and take up the weight of the chain. Break the joining shackle.

- Walk back the 2nd easing wire to bring the end of the cable clear of the hawse pipe.

- Recover this end of the cable using rope hawsers through the Panama lead.

- Now walk back the anchor chain through the hawse pipe and the cable is now ready for towing or mooring operation.

How will you go about anchoring in high water?

The strongest flood and ebb currents usually occur before or near the time of the high and low tides. The weakest currents occur between the flood and ebb currents and are called slack tides. I will check the timings of high water and low water. If anchoring during the high water time, I will experience strong current. I will go about anchoring the normal way but stemming the tide and giving bold engine movements to maintain ship’s position while anchoring. I will proceed with caution taking into account the direction and strength of the current and also note the direction of the other anchored vessels.

Also, if the tidal range is high and tidal current is very strong in that anchorage, I will increase the scope of the cable and pay out one or two shackles more considering the increase in the water depth at high tide and also the effect of current on the vessel. Also, I will keep the engines always ready while at anchor to give bursts of short kicks if excessive load comes on the cable due to the current.

‘anchor is dragging’. State your actions.

• I will immediately send anchor party forward, get engines ready, and increase bridge manning.

• I will stop all operations and cast off any barges or boats alongside.

• I will inform the VTS and Port control on VHF and request for pilot and tugs if required.

• I will make securite announcement on VHF to alert other vessels in the vicinity.

• I will have Flag Y hoisted.

• I will quickly ascertain vessel’s speed and time in hand before vessel will collide with

any vessel in vicinity or run aground.

• Accordingly, I will decide if I have sufficient time to heave up the anchor and proceed to another anchorage area or re-anchor in the same area.

• If I do not have enough time, I will let go the other anchor to get extra holding power. I will do this when the ship has sheered away from the first anchor. I will also veer more cable on the first anchor.

• I will use engine movements to maintain the vessel’s position and prevent the cable from growing to long stay.

• If collision is imminent, I will try to reduce the impact by rigging fenders, hawsers, etc. and request the other vessel to do so too.

• After situation is under control, I will inform the Company, Agents, charterers, etc.

• I will save VDR data and make appropriate entries in the Log Book.

You vessel is dragging anchor at Dahej. State your actions. Which flag will you hoist?

Dahej has a tidal range of about 10m. The tidal stream in the area is very strong. I will do the following in case my vessel is dragging anchor:

• I will already have my engines ready at all times at anchor.

• I will immediately send the anchor party forward and try veering some more cable, giving ahead kicks on the engine so as to avoid any load on the windlass.

• After observing, if the vessel is still dragging her anchor, I will drop the other anchor or heave up the first anchor and re-anchor at another location.

• If the current is too strong for re-anchoring, I will drift at a safe location and anchor during the slack tide. I will keep the VTS and port authorities informed.

• I will hoist Flag Y – which means I am dragging anchor.

MOORING & BERTHING:

Explain with diagram Standing and Running Moor? Which one is better?

Running Moor:

Let us say the vessel is required to moor with bridge along the Line AB. The stream is from ahead and we require five shackles on the Port anchor and four shackles on the starboard anchor. The procedure is as follows:

• The vessel is headed into the stream or wind. When both of them are present, vessel must be headed to the one that has a stronger effect.

• The starboard anchor is let go on the run (with headway), when the vessel is roughly 4 shackles minus half of ship’s length away from Line AB.

• The cable is paid out as the vessel moves upstream or upwind. It is paid out (veered) to a length of nine shackles, the sum of two lengths. The cable is not allowed to tighten, or else the bow will cant to starboard.

• When the vessel moves to position 2, she then falls astern with the tide. The port

anchor is then ‘let go’.

• Five shackles are veered on this riding cable (port anchor) and five shackles are weighed on the starboard cable. The vessel is then brought up on her riding cable at position 3.

In a cross wind, the weather anchor is first let go. If the lee anchor is let go first then the vessel will drift across her cable & the cable will grow under the ship. In calm weather, the port anchor is better to be dropped at Position 2 as any astern movement to reduce headway will cant the stem away from the anchor.

Standing Moor:

Let us say the vessel is required to moor with bridge along the Line AB. The stream is from ahead and we require five shackles on the Port anchor and four shackles on the starboard anchor. The procedure is as follows:

• The vessel is headed into the stream or wind. When both of them are present, the vessel must be headed to the one that has a stronger effect.

• With sufficient headway, the vessel is taken to Position 1, which is roughly 5 shackles plus half ship’s length beyond line AB.

• At Position 1, the port (lee) anchor is ‘let go’. As the vessel drifts downstream, the port cable is veered upto 9 shackles, the sum of two lengths.

• When she is brought up gently on her port cable, at Position 2, the starboard (weather)

anchor is ‘let go’. Before doing this, engines can be used to take sternway off the vessel, if any. The helm can be ordered away from the released anchor.

• Vessel then moves to the required Position 3 by veering the starboard cable upto 4 shackles and heaving in four shackles on the riding cable (port anchor)

• During the middling of the vessel to the required position, the engines may be used ahead or astern to reduce stress on the windlass.

• In calm weather, it is better to drop the Port anchor first at Position 1, as any astern movement to reduce headway will cant the stem away from the anchor.

I feel that the standing moor is better than running moor as it is comparatively safer since the anchor is let go after the vessel has stopped. This reduces the possibility of damage to the anchor which is higher when anchored under headway.

Explain with diagram Baltic moor and Mediterranean moor.

Baltic Moor:

This moor is employed alongside a quay where strong onshore winds are experienced and when construction of the berth is not sufficiently strong to withstand ranging of vessel in bad weather. The vessel should approach the berth with the wind on the beam or slightly abaft the beam. The procedure is as follows:

• Before the approach has begun, a stern mooring wire is passed from the after ends on the poop, along the offshore side, outside and clear of everything. The wire is secured with ship’s rail in bights using light seizings.

• The offshore anchor is cock-a-billed and a man is sent overside on a chair to secure the wire with the anchor, preferably at the shackle. The aft end of the wire is sent to a warping drum, ready for heaving up slack wire.

• The vessel is manoeuvred to a distance off the berth of 2 or 3 shackles of cable. This distance will vary with wind force & weather conditions.

• When the stem is about the middle of the final position, and vessel has lost headway, the offshore (stbd) anchor is let go with the bow slightly canting inshore (to port).

• The weight of the anchor and cable will cause the light seizings to part and as the cable pays out, so will the stern mooring wire.

• The wind will push the vessel alongside, while the cable and the stern wire are paid out evenly together. Ship’s fenders must be used along the inshore side.

• Head lines and stern lines must be passed as soon as practical and secured on the bitts before taking the weight on the anchor cable and the stern mooring wire.

• Once the inshore (port) moorings are made fast, the anchor cable and the stern mooring wire can be tightened

so as to harden up the inshore (port) moorings.

• When the vessel has to depart the port, unless she is fitted with bow thrusters, the Master may encounter difficulties in clearing the berth. However, heaving on the anchor cable and on the stern mooring will allow the vessel to be bodily drawn off the quay. Once clear of the berth, full use of engines & helm can be made to get under way.

• It is very important to let go the offshore anchor at the best possible position. If the anchor is let go too far off the quay, the stern wire will be of insufficient length and the ship will fail to reach the berth. If this happens, the anchor must be weighed and the manoeuvre repeated.

Mediterranean Moor:

This moor is carried out usually for one of two reasons – either quay space is restricted and several vessels are required to secure or a stern loading/ discharge is required.

The object of the manoeuvre is to position the vessel stern to the quay with both anchors out in the form of an open moor. The stern of the vessel is secured by hawsers from the ship’s quarters to the quay. The manoeuvre greatly depends on the prevailing wind but let us assume calm weather with no current or wind.

• The approach should preferably be made with the berth on port side, as parallel to the quay as possible. Let go the offshore (stbd) anchor. Main engines should be ahead and dead slow. The bow may be initially made to cant towards the berth while letting go the offshore anchor.

• The vessel continues to move ahead. Starboard helm is now applied as the starboard cable is veered.

• Once the vessel begins to swing to stbd, the engines are stopped. On reaching position 3, the engines are put astern and the port anchor is let go.

• As the vessel comes astern, transverse thrust swings the stern to port towards the berth and the port side cable is veered, with any slack cable on the offshore anchor heaved.

• The vessel is then manoeuvred using engines & cable operation until she is at within heaving line distance of the quay. Once she is within heaving line distance, stern lines are sent away.

• This method is difficult in bad weather and also has a possibility of fouling anchor cables, especially when other vessels are moored in a similar manner close by. It is also not practical in deep water or places with large tides.

What is spider mooring?

Spider mooring systems are multi-point mooring systems that moor vessels to the seabed using multiple mooring lines. Normally, combination of three mooring lines (or as advised by the mooring master) are used on one buoy each out of the four buoys that are used.

While the vessel is in a fixed heading, the bow typically heads into the dominant environment which is usually the direction where the largest waves are coming from.

Spider mooring systems with buoys are called conventional buoy moorings (CBM systems).

Procedure for spider mooring:

- In this method, the bow of the ship is secured using both her anchors whereas the stern is secured to the buoys around it.

- In the approach, the vessel firstly approaches the final berthing position from forward at an angle of 90 degrees to her final direction of berthing.

- The starboard anchor is then let go at a pre-decided spot while the ship is making headway. Required amount of cable is paid and the stern moments are given simultaneously to stop the vessel.

- Once the vessel is stopped in water, port anchor is let go and thus the vessel positions her stern along the centerline bifurcating the buoys. For aligning the vessel along the centerline, port cable is paid out and starboard cable is heaved with stern propulsion. The helm and engines are to be carefully used during this manoeuver to ensure that the stern is swinging clear off the buoys.

- Then, once in position, set of 3 mooring lines are passed and made fast to each buoy on the port and starboard bow and quarter and vessel is made fast.

- While unberthing, the anchor cables are heaved in to move the vessel forward and weight is taken on windward lines while casting off other lines to prevent swinging of the stern into the other buoys.

- This manoeuver requires skill and efficient operation of ship’s crew as well as of the

mooring equipments as often weight of the lines can be immense.

How do you plan for anchoring and berthing a ship and how does the prevalent wind, sea and current affect your plan?

Planning: As with any other shiphandling operation, a proper plan should be developed prior to anchoring. The planning involves careful scrutiny of the chart of the area the vessel is proposing to anchor. Items that need to be considered are:

- Local customs and practice such as any port regulations that designate anchorage areas for the type and size of ship.

- Direction and strength of wind and current

- Depth of water.

- Manoeuvring room for the approach.

- Swinging room at the anchorage.

- Type of bottom (holding ground, good or bad)

- Location of navigational hazards and distance from the lee shore.

- Conditions affecting visibility, weather and currents.

- Length of time the vessel intends to stay at anchor.

- Determining the scope of the cable.

- If possible, the number and location of other ships at anchor. As the ship approaches the anchorage, this will become apparent and may require the approach plan to be altered. Hence, plan must remain flexible.

The prevailing wind and current will affect the manoeuvrability of the vessel. Stronger the wind and current, more it will impact the ship’s movement. Slower the vessel’s speed during approach more will be the effect of wind and current. Wind and current will also affect the stopping distance of the ship and may require a change of speed due to the changing conditions. The plan may require amendment due to the change in the direction or strength of the wind and current.

Observation of other ships at anchor will give the shiphandler a good idea of how the wind and current are affecting the ships. It will also give an indication if there are any ships that are underway at the anchorage.

The direction of wind and current will determine the preferred approach direction and the final heading after anchoring. The shiphandler should try and approach the anchorage at a steady heading while slowing down. As the ship slows down, the effect of set and drift will increase. It may be required to pass downstream and to leeward of other anchored ships and then round up to get on the desired heading. When approaching an anchorage, the shiphandler should never pass upstream or to windward of other ships.

Describe the procedure for berthing with onshore wind and current from behind.

• Stop the vessel over the ground in a position with the ship’s bow roughly in line with

the middle of the berth. Let go offshore anchor.

• The onshore wind will push the vessel towards the berth. Control the rate of approach towards the berth by astern movements to counter the current from behind. While doing so, check and ease out anchor cable as required.

• Try and keep the vessel parallel to the berth. Check cable when vessel is within heaving line distance of the berth. Make fast fore and aft. With current from stern, it will be preferred to make fast forward springs and stern lines first so as to position the vessel correctly.

• Once the vessel is all fast, the anchor cable can be slackened down.

• Alternatively, Baltic mooring can be carried out if vessel design allows and if required by the Pilot or Port.

• It will better to turn around fully and stem the current as it will give the vessel better directional stability.

How will you berth your ship with strong onshore wind and no tugs?

• Stop the vessel over the ground in a position with the ship’s bow roughly in line with

the middle of the berth. Let go offshore anchor.

• The onshore wind will push the vessel towards the berth. Control the rate of approach towards the berth by engine movements and checking and easing out anchor cable as required. Try and keep the vessel parallel to the berth.

• Check cable when vessel is within heaving line distance of the berth. Make fast fore and aft. Once the vessel is all fast, the anchor cable can be slackened down.

• Alternatively, Baltic mooring can be carried out if vessel design allows and if required by the Pilot or Port.

How will you berth your ship with stern current and no tugs?

I will swing my vessel around and stem the current so as to have better maneuvering efficiency. If swinging room is not available, I will do the following:

• I will approach staying parallel to the berth.

• If I have to berth the vessel port side alongside, then I will give hard starboard to move the bow away from the berth. (I will use B/T for this if available).

• Once the bow is away, I will give stern movement and once the stern is within the heaving line distance, stern ropes will be passed.

• Once the stern ropes are passed, the current from behind will swing the bow to port. Swing needs to be checked using engines (transverse thrust will assist) and rudder or port anchor can also be dropped at short stay.

• Once the bow is within heaving line distance, head lines can be passed and all lines can be made fast.

• If vessel has to berth starboard side alongside, the procedure remains the same. However, once the stern lines are passed, the bow will swing to starboard and any astern movement to counter the current will increase the swing to starboard due to transverse thrust. In such a case, port anchor must be used to counter the swing to starboard.

How will you decide the number of tugs required for berthing or unberthing? How to know what bollard pull to be used on ships?

Factors to take into account when determining the number of tugs required:

• Practice in the port for the particular size of ship and the designated berth.

• Draft and Under keel clearance

• Anticipated strength & direction of wind and current & its likely effect on berthing.

• Windage area of the ship

• Stopping power and handling characteristics of the ship.

• Manoeuvring room available.

• State and height of tide

• Proximity of other ships and quay structures

• Bollard pull and condition of the available tugs

• Vessel’s condition (loaded/ballast), propulsion power, availability of thrusters, etc.

Bollard pull of the tugs must be sufficient for the size (displacement) of the ship and also sufficient enough for the manoeuver intended. If the bollard pull is sufficient, one tug forward and one tug aft is usually sufficient for a small size ship. If bollard pull is less (for bigger ships) two tugs must be required forward and two tugs aft. Usually, it is decided by the Port Authority and Pilot considering the size of the ship and prevailing circumstances. The bollard pull of the tugs required varies from port to port and on vessel’s condition (loaded/ballast). Usually, for a ship of about 150m in length, without bow thrusters, two tugs (F+A) of more than 25 T Bollard pull each will be considered sufficient. The bollard pull must never exceed the SWL of the bollard used to make fast the tug. If the tug’s bollard pull is greater than the SWL of the bollard, pilot must be informed to not exceed the SWL of the bollard when the tugs are pulling.

You have to berth starboard side alongside and the berth is on your starboard side. Current is from astern. You have tugs to assist you. Explain the procedure for berthing.

• It is preferred to berth stemming the current as it provides for better handling. If that is not possible, following steps can be taken to berth vessel using tugs and current from stern:

- The aft tug must be made fast to the port quarter and forward tug to the port bow.

- The vessel must be slowly maneuvered parallel to the berth keeping sufficient distance from the jetty.

- Bold astern movements will be required if the stream is strong from astern. This will cause the bow to swing to starboard towards the berth due to transverse thrust. The forward tug will be more effective when engines are run astern and hence, must pull only minimum required to counter the transverse thrust when required. The forward spring lines can then be passed. This will help to counter the forward movement of the vessel due to the current.

- Once the bow is in, the stern will move away from the jetty due to the effect of the current. The aft tug is now required to push the stern towards the jetty to counter the effect of the current. The stern lines are then passed.

You are port side alongside in Mississippi river. There is bridge behind you and 3 knots current from ahead. Explain the procedure for unberthing and turning the vessel.

• The vessel must single up to a head line and aft spring.

• The head line must be eased first and rudder must be put to starboard.

• With the tidal effect between the bow and the quayside the

ship’s bow should pay off.

• Now the aft spring should be eased slowly as the vessel’s

stern moves away from the quay.

• As the vessel is moving away from the quay, engines must be put on slow ahead with rudder still hard starboard and head line must be taken in. Thereafter, the aft spring must be taken in as well.

• The engines and rudder must be used as appropriate to execute the turn. Before completing the turn, the engines must be put to dead slow ahead as the current will be from the stern and will increase the SOG of the ship.

Northerly current, offshore wind, tugs available, vessel is 5 miles from the berth. Berth is at port side. How will you approach the berth and at what speed?

I will approach the berth with safe speed depending on various factors such as loading condition of the vessel, stopping distance, proximity of hazards, UKC, availability and efficiency of tugs, etc.

When 5 NM from the berth, I will be on maneuvering RPM and commence reducing speed to around 8 knots. When 3 NM from the berth, as recommended in my Company SMS, I will commence slowing down so that when I reach the stopping distance from the berth, I am at dead slow ahead and when 4L from the berth I will have minimum speed to maintain steering (around 3 knots). I will increase braking using engines running it astern and using tugs as required.

I will plan my approach depending on the strength of the off shore wind and the current. Ideally, since I have tugs forward and aft, I will go parallel to the berth (around 2-3 times the beam) and then ask the tugs to push the vessel bodily against the offshore wind. If the current is from stern, I will position the ship parallel to the jetty at a position aft of my final position so that current will work in favour and bring me to the final position. If the current is from ahead, then I will position the ship parallel at a position forward of the final position.

At all times, I will keep track of the distance from the berth and the ship’s speed. If I feel at any point, the ship’s SOG is excessive, I will use bold engine movements and tugs to kill the speed and safely berth the vessel.

You are on a 200m long vessel with right handed fixed pitch propeller. No B/T, No tugs, no current, no draft restriction and sufficient sea room all around the basin. Berth is your port side and strong onshore wind from your stbd beam. How will you berth your ship stbd side alongside?

I will not consider it safe to berth a ship 200m long without the assistance of tugs when the vessel is not even fitted with a B/T. I will wait for the port authorities to give me tugs for berthing the vessel safely. For a small vessel which has more maneuverability, following procedure can be adopted:

• Turn the vessel to starboard giving ahead kick and rudder hard to starboard.

• Once the vessel has the wind right ahead, put rudder midship and give astern kick. Transverse thrust will cause the ship to swing to starboard and since the pivot point is now aft, the wind will also assist in the starboard turn. Check on the swing using the rudder to stay parallel to the berth.

• Stop the vessel over the ground in a position with the ship’s bow roughly in line with the middle of the berth. Let go offshore anchor (port anchor).

• The onshore wind will push the vessel towards the berth. Control the rate of approach towards the berth by engine movements and checking and easing out anchor cable as required. Try and keep the vessel parallel to the berth.

• Check cable when vessel is within heaving line distance of the berth. Make fast fore and aft. Once the vessel is all fast, the anchor cable can be slackened down.

• Alternatively, Baltic mooring can be carried out if vessel design allows and if required by the Pilot or Port.

You have to berth stemming a strong current. Which lines will you pass first?

Spring lines aft and head lines will be passed first in order to prevent the falling back of the vessel.

MANOUEVRING:

What is wheel house poster? Describe the details you get in the wheelhouse poster?

Wheel house poster is a poster giving information regarding the ships general particulars and detailed information describing the manouevring characteristics of the ship.

As per IMO Resolution A.601(15), the wheel house poster should be permanently display in the wheelhouse. It should be of such size to ensure ease of use. The maneuvering performance of the ship may differ from that shown on the poster due to environmental, hull and loading conditions.

Details contained in the wheel house poster are as follows:

- Ships particulars: Name, Call sign, Gross Tonnage, Net tonnage, Max Displacement, DWT, Block Coefficient at Summer full load draft, etc.

- Steering particulars – Type of rudder(s), maximum rudder angle, time hard-over to hard-over with one and two power units, minimum speed to maintain course when engine is stopped, etc.

- Propulsion particulars – Type of engine and power, type of propeller, RPM and speeds in loaded and ballast condition for various engine orders, critical RPM, time for full ahead to full astern, time from stop engine to full astern, max. no. of consecutive starts, and astern power w.r.t. % of ahead power.

- Anchor chain details i.e. number of shackles in port & stbd anchor and maximum rate of heaving them (min/shackle).

- Thruster particulars – Bow or stern thrusters, its power, speed above which it is not effective, turning rate at zero speed, etc.

- Drafts at which manoeuvring data observed in loaded and ballast condition.

- Turning circles at maximum rudder angles in loaded condition for deep and shallow waters, and turning circle at maximum rudder angles in ballast condition for deep waters.

- Stopping distances and times in loaded and ballast condition.

- Emergency maneuvers for rescue of man overboard.

What all manoeuvring characteristics will you find on the Bridge? Out of that, which is the most important to you as a Master? Can two sister ships have different data?

IMO Resolution A.601(15) on Provision and display of manoeuvring information onboard ships recommends the manoeuvring information to be presented as follows:

• Pilot Card –to be filled in by the Master, is intended to provide information to the pilot on boarding the ship. The information should describe the current condition of the ship, with regard to its loading, propulsion and manoeuvring equipment, and other relevant equipment.

• Wheelhouse Poster – should be permanently display in the wheelhouse. It should contain general particulars and detailed information describing the manoeuvring characteristics and should be of such size to ensure ease of use. The maneuvering performance of the ship may differ from that shown on the poster due to environmental, hull and loading conditions.

• Manoeuvring Booklet – should be available onboard and should contain comprehensive details of the ship’s manouevring characteristics and other relevant data. It should include the information shown on the wheelhouse poster together with other available manouevring information. Most of the information in the booklet can be estimated but some should be obtained from trials.

According to me, the most important thing in the manouevring characteristics is the stopping distances and the turning circles.

Two sister ships may have slightly different data based on the their drafts, density of water, and different environmental conditions. However, the differences will not be substantial.

What is the requirement for maneuverability information on Bridge?

As per SOLAS II-1 / 28 – Means of going astern, the stopping times, ship headings and distances recorded on trials, together with the results of trials to determine the ability of ships having multiple propellers to navigate and manoeuvre with one or more propellers inoperative, shall be available on board for the use of the master or designated personnel. This information is provided in the form of Manouevring Booklet in the format as given in IMO Resolution A.601(15).

Describe rudder cycling.

Rudder cycling can be used as an alternative to crash stop when there is more time and distance available to deal with the situation and the ship has sufficient sea room to carry out this maneuver. It is a very effective method of stopping the ship while maintaining her directional movement. It uses the resistance of water on underwater hull area to reduce the speed of the ship. Let us consider a vessel proceeding at full ahead and needs to stop. With Port side safer than starboard side; we must carry out the following actions:

• Put the rudder hard to port. When the ship has turned to 200 from the original course, put the telegraph to half ahead.

• When the ship’s heading is 400 from the original course, put rudder hard to stbd.

• When the ship’s heading just starts to turn to starboard side, put the engines on slow ahead.

• When the ship’s heading has returned to original course, put rudder hard to port.

• When the ship just starts to turn to port, put the engine to dead slow ahead.

• When the ship’s heading returned to original course, put the rudder hard to starboard to check some of the port swing.

• When the ship still has some rate of turn to port, go full astern on engines to stop the ship. Subsequently, put rudder to midship and stop engines.

What is pivot point? How, where and when will you use it?

A ship rotates about a point situated along its length, called the ‘pivot point’. When a force is applied to a ship, which has the result of causing the ship to turn (for example, the rudder), the ship will turn around a vertical axis which is conveniently referred to as the pivot point.

The position of the pivot point depends on a number of influences. With headway, the pivot point lies between 1/4 and 1/3 of the ship’s length from the bow, and with sternway, it lies a corresponding distance from the stern. In the case of a ship without headway through the water, the pivot point will be near the midship. The pivot point traces the path that the ship follows.

Pivot point is used in the following cases:

• When working with tugs, the effectiveness of the tugs will depend on the position of the pivot point among other factors.

• When using the bow thrusters, the effectiveness of the thruster will depend on the position of the pivot point among other factors.

• When turning using rudder and engines in a congested area

• When using anchors for berthing

What do you know about turning circle, tactical diameter, head reach, track reach and what are the various limits assigned to them?

The turning circle is the roughly circular path traced by the ship’s centre of gravity (COG) during a full 3600 turn with constant rudder angle and speed. Throughout the turn, her bow will be slightly inside the circle and stern a little outside the circle. Due to some side slip, when the helm is first applied, the circle does not link up with the original course.

During the turn, the vessel suffers some loss of speed. After turning through 900, about 1/4th of her original speed is lost. After turning through a total of 1800, about 1/3rd of the original speed is lost. Thereafter, speed remains roughly constant.

Advance is the distance travelled by the COG of the ship, along the original course, measured from the time the rudder is put over until the vessel’s head has turned by 900.

Transfer is the distance travelled by the COG of the ship, measured in the direction perpendicular to that of the original course, from the original track to a point where the vessel has altered her course by 900.

Tactical Diameter is the distance travelled by the COG of the ship, measured in the direction perpendicular to the original course, from the time the rudder is put over until the ship has altered her course by 1800. It is the greatest diameter traced by the vessel from commencing the turn to completing the turn.

Stopping distance is defined as the minimum distance that a vessel may be seen to cover to come to rest over the ground. Normally, stopping distances are provided from full ahead to stop engine and from full ahead to crash full astern i.e. crash stop.

‘Track reach’ is defined as a distance along the vessel’s track that the vessel covers from the moment the ‘full astern’ or ‘stop engine’ command is given until the ship changes the sign of the ahead speed or stops dead in the water. Track reach is usually less than 15 L. It can be more than 15 L but never exceed 20 L.

‘Head reach’ is defined as the distance along the direction of the original course measured from the moment the ‘full stern’ or ‘stop engine’ command was given until the ship is dead in the water.

As per Resolution MSC.137(76), on Standards For Ship Manoeuvrability,

• The advance should not exceed 4.5 ship lengths (L)

• The tactical diameter should not exceed 5 ship lengths.

• The track reach should not exceed 15 ship lengths. However, this value may be modified by the Administration where ships of large displacement make this criterion impracticable, but should in no case exceed 20 ship lengths.

The above Standards should be applied to ships of 100 m in length and over, and chemical tankers and gas carriers regardless of the length. If they undergo repairs, alterations or modifications, which, in the opinion of the Administration, may influence their manoeuvring characteristics, the continued compliance with the Standards should be verified.

How is the turning circle different in different conditions? (load/ballast, deep/shallow waters, port/stbd turning, etc)

Factors affecting the turning circle:

- Displacement – Loaded ship will have increased draft and displacement, thus more lateral resistance. Because of this, turning circle of the loaded ship will be more than that of the same ship in ballast condition.

- Trim – When a ship has trim by stern, pivot point is further aft than that if she was on even keel. Due to this, turning circle is larger with a stern trim than with a trim by head.

- List – The effect of list on turning circle is such that the vessel will turn more readily towards the high side. That means the vessel will have a smaller turning circle on the high side.

- Shallow Waters – When a vessel turns in shallow waters, her turning circle is bigger. This is because of restriction of water flow due to lesser under keel clearance. The rudder force has to overcome larger lateral resistance and therefore is less efficient. Also, at the bow, because of reduced UKC, the water which would normally pass under the ship gets restricted. This results in build-up of pressure – both at the head of the ship and port bow (when turning to stbd). This pressure pushes the pivot point abaft thus reducing the turning lever.

- Port/Stbd Turn – Turning circle to port and starboard are nearly the same. Right handed propeller will have circle to port slightly shorter in radius than circle to starboard due to transverse thrust.

What was the advance, transfer, tactical diameter, head reach, track reach of you last ship?

At Harbour Full Speed (Man. RPM 95), with rudder to 350 starboard / port:

• Advance = 466m (3.3L) / (3.3L)

• Tactical Diameter = 532m (3.8L) / (3.7L)

• Transfer = 228m / 215m

At Harbour Full Speed (Man. RPM 95), with full astern command:

• Head Reach = 1207m

• Track Reach = 1212m (8.6L)

How is the ships speed on various engine orders calculated?

Ships speed trials are carried out during the sea trials to calculate the speed of the ship to ensure that it is as per the requirements of the contract between the ship owner and the shipyard.

- The test is carried out at a minimum of 3 powers – such as 75%, 85%, 100% MCR (Maximum Continuous Rating) or any other power as per the contract.

- The speed at each power is measured using the GPS by running the ship in two opposite directions (called double run).

- Now the speed measured at suppose three powers are plotted to give a speed-power curve.

- Finally, from the curve, the speed corresponding to the required power as outlined in the contract is noted.

Ships speed at various RPM’s is given in the manouevring booklet. It is calculated in the following manner:

• The ship is run at various RPM’s and the ship’s speed at those RPM’s are noted.

• Along with the speed, various other engine parameters such as engine load, scavenge pressure, t/c RPM, etc. are also noted and a table is prepared.

• Same in done for the vessel in loaded condition or data is taken from a loaded sister vessel.

• Only the speeds at the RPM’s corresponding to the engine orders (DS, S, H, Full) are tabulated and displayed on the Bridge near the telegraph.

What is the difference between Pilot card and maneuvering poster on bridge?

The pilot card is to be filled in by the Master every time before the pilot boards the vessel and presented to the pilot upon boarding. It is intended to provide the current information to the pilot describing the present condition of the ship, with regard to its loading, propulsion and manoeuvring equipment, and other relevant equipment. It also includes a small checklist of certain items if are available and ready for use. Certain information entered in the Pilot card is obtained from the wheel house poster.

The Wheelhouse Poster on the other hand is permanently displayed in the wheelhouse containing fixed information such as general particulars, manoeuvring characteristics of the ship, etc. The actual maneuvering performance of the ship may differ from that shown on the poster due to environmental, hull and loading conditions. The wheel house poster is prepared by the yard and given to the vessel after the sea trials are conducted.

What is yaw test? How and when is it carried out? How will you use information from this?

Yaw tests are the tests that are carried out during the sea trials. It comprises of the zig-zag test and pull-out manoeuvre tests at full load or ballast condition. The results are the tests are given in the form of a diagram of heading changes and rudder angle. The tests are carried out during the sea trials before the vessel is delivered.

It can be a 100 zig-zag test or a 200 zig-zag test. The test is carried out in order to check

the rudder’s initial response time, yaw checking time and overshoot angle.

The procedure of the test is described in MSC./Circ.1053 and the test is carried out in the following way:

• The ship is brought to a steady course and. speed according to the specific approach condition. The recording of data starts.

• The rudder is ordered to 10° to starboard. (for a stbd test)

• When the heading has changed by 10° off the base course, the rudder is shifted to 10° to port.

• The ship’s yaw will be checked and a turn in the opposite direction (port) will begin.

• The ship will continue in the turn and the original heading will be crossed. .

• When the heading is 10° port off the base course, the rudder is reversed (put to starboard) as before.

• The procedure is repeated until the ship heading has passed the base course no less than two times.

• Recording of data is stopped and the manoeuvre is terminated.

The main objective of conducting this test is to check the ship response in changing its course in response to a given rudder angle along with the variation in Yaw rate.

Information useful to Master from this test:

- Initial Turning Time after the helm order is given.

- Overshoot angle – the excess angle of heading reached by ship in its previous direction (after rudder is applied). It gives an indication as to how much the vessel will overshoot when rudder is applied in the opposite direction. This can be useful when manoeuvring and turning in congested waters close to obstructions and other navigational hazards.

- Time taken to check Yaw.

Pull out manoeuver: After a turning circle with steady rate of turn the rudder is returned to midship. If the ship is yaw stable, the rate of turn will decay to zero for turns both port and starboard. If the ship is yaw unstable, the rate of turn will reduce to some residual rate of turn. The pull-out maneuver is a simple test to give a quick indication of a ship’s yaw stability, but requires very calm weather. If the yaw rate in a pull-out maneuver tends towards a finite value in single-screw ships, this is often interpreted as yaw instability, but it may be partially due to the influence of wind or asymmetry induced by the propeller in single-screw ships.

What is first and second overshoot? Where will you find this?

First and second overshoot angles are calculated during the zig-zag test performed at sea trials of the vessel. First overshoot angle is the excess angle of the heading reached by the ship in its previous direction after rudder is applied. Second overshoot angle is the excess angle of heading reached by the ship in the second cycle of the test. Least overshoot angle is desirable for better controllability.

This information will be in the ‘Results of Sea Trials’ under the ‘Zig-zag test results’ given to the ship by the shipyard on delivery and made part of the Manouevring Booklet.

What are the provisions for display of information on Bridge?

The provision for display of manouevring information on Bridge is given as recommendation in IMO Resolution A.601(15).

It requires maneuvering information to be presented as:

• Pilot card

• Wheel house poster

• Manoeuvring booklet

You are in a TSS and VTS suddenly asks you to stop your vessel immediately. The vessel ahead of you is one mile away. State your actions.

• I will always have situational awareness and monitor the speed of the vessel which is close to my own vessel. I will ask the VTS the reason for such a request.

• To stop the vessel in an emergency, I can use crash stop manoeuver or rudder- cycling.

• If sufficient sea room is available at the sides, I can take a full turn and go in the opposite lane and do the opposite course.

• If required, I can also enter the traffic separation zone or inshore traffic zone to avoid immediate danger.

How will you use turning circle to your advantage?

Information in the turning circle is useful and can be advantages in the following manner:

• The advance helps to identify how far the vessel will go in the same direction after the helm is put hard over.

• The tactical diameter helps to identify the swinging room required to safely complete a full turn of the vessel. It is particularly useful in tight turning situations such as in berthing, turning with other vessels or obstructions in close vicinity, etc.

• It helps to mark the Point of no return on the chart.

• It difficult situations where a danger lies ahead at a distance less than the stopping distance, the danger can be avoided by turning the vessel if sufficient side reach is available.

Pilot is onboard and no manoeuvring diagram / wheel house poster available on bridge. State your actions.

• I will provide all the information as required in the Pilot Card using the Manouevring booklet supplied by the yard.

• I will make copies of the relevant pages of the Manouevring Booklet and present it to the Pilot if required.

• I will inform the Company and get the required information as soon as possible.

• I will inform the Pilot politely that the diagram / poster is not mandatory but recommendatory as per IMO Resolution A.601(15) and that SOLAS II-1/28 requirement of manouevring booklet has been complied with. However, I will assure the Pilot that the needful shall be done on priority basis.

• Later, I shall make an ISM observation and send the report to Office.

How many consecutive starts are required for a main engine? Where will you find this information?

As per IACS requirements on Starting Arrangements of Internal Combustion Engines,

• Where the main engine is arranged for starting by compressed air, two or more air compressors are to be fitted. At least one of the compressors is to be driven independent of the main propulsion unit and is to have the capacity not less than 50 % of the total required.

• The total capacity of air compressors is to be sufficient to supply within one hour the required quantity of air by charging the receivers from atmospheric pressure and this capacity is to be approximately equally divided between the compressors.

• Where the main engine is arranged for starting by compressed air, at least two starting air receivers of about equal capacity are to be fitted which may be used independently.

• The total capacity of air receivers is to be sufficient to provide, without their being replenished, not less than 12 consecutive starts alternating between Ahead and Astern of each main engine of the reversible type, and not less than six starts of each main non-reversible type engine connected to a controllable pitch propeller. The number of starts refers to engine in cold and ready to start conditions.

• This information regarding maximum consecutive starts of a main engine are provided in the wheel house poster, manoeuvring booklet and also in the Ship’s manuals. It has to be entered in the Pilot Card and Master pilot information exchange form.

What is the difference between an accelerated turn and a constant radius turn?

• Constant radius turn is when rudder is applied such that the vessel swings in an arc about the centre of a circle having the required radius.

• Accelerated turn is when the ship is turned using a constant rudder angle and the engine speed increased during the turn.

How long will you take to complete a full turn?

Well, it depends on several factors such as rudder angle applied, loading condition of the ship, depth of water (shallow/deep), environmental factors such as wind, waves and current, direction of use (port turn will be faster due to transverse thrust), etc.

The information can be obtained from the sea trials data given in the manouevring booklet. It is given as a table for port and starboard turn giving the turning angle, time taken from order to reach that angle, the advance and transfer for each angle. My last ship took 5 mins 50 seconds to complete a port turn and 6 mins 20 seconds for a starboard turn.

RUDDERS AND PROPELLERS:

What is CPP? Can a CPP run on zero pitch?

CPP stands for Controllable pitch propeller. Vessel’s fitted with CPP have the engines running in one direction (usually clockwise or right hand). The vessel’s speed is controlled by varying or reversing the pitch of the propeller. Blade Pitch or simply pitch refers to the angle of the blade in a fluid. Propeller pitch is the theoretical distance (without slip) that the propeller would move forward with every full revolution of 3600 .

In CPP, it is possible to alter the pitch by rotating the blade about its vertical axis by means of mechanical and hydraulic arrangement. This helps in driving the propulsion machinery at constant load with no reversing mechanism required as the pitch can be altered to match the required operating condition. In other words, the vessel’s engines do not have to be stopped & reversed to go astern, giving the user infinite choice of speeds. Thus, the manoeuvrability improves and the engine efficiency also increases, reducing fuel consumption. However, it is a complex and expensive system from both installation and operational point. A distinct ship-handling advantage is obtained by being able to stop in the water without having to stop main engines.

Yes, a CPP can run on zero pitch. The vessel would be stopped but the propeller would be sill turning at zero pitch. Since the CPP is always turning even in stop position with zero pitch, great care must be taken when working with stern lines as they could be fouled in the propeller.

What is transverse thrust? How does it affect the ship going ahead and astern? Consider a ship with right handed fixed pitch propeller.

The thrust of a propeller blade is divided into two components:

- Fore and aft component

- A very small athwartship component

The latter is called transverse thrust or starting bias which is caused by the wheeling effect and helical discharge. For a right handed propeller, while going ahead, the bow cants to port, the swing decreases as way is gathered. While going astern, the bow cants strongly to stbd and will continue to do so until correcting helm is used.

Explain in short the various types of rudders.

Unbalanced Rudder: These rudders have their stocks attached at the forward most point of their span, and runs from the top end to the bottom end of the rudder. The rudder is defined as ‘unbalanced’ because the whole of the surface area is aft of the turning axis. It is no longer used for large constructions because of alignment issues but is occasionally seen on smaller vessels and coastal barges. Torque required to turn the rudder is way higher than what is required for a corresponding balanced rudder

Semi-balanced Rudder: The name ‘semi-balanced’ itself implies that the rudder is partly balanced, and partly unbalanced. It also refers to the amount of surface area forward of the turning axis which is in between that of a balanced and unbalanced rudder. If the proportion of surface area is less than 20 % forward of the axis, then the rudder is said to be semi-balanced. This is a very popular rudder for modern ships, especially for the container type vessel and twin-screw vessels.

Balanced Rudder: The surface area of the rudder is proportioned either side of the ‘bolt axle’. The amount of surface area will vary between 25-30% but does not exceed 40% forward of the axle. The advantage of a balanced rudder is that a smaller force is required to turn it, so that smaller steering gear may be installed at lower running cost. This is because the COG of the rudder will lie somewhere close to 40% of its length from its forward end, thus requiring less torque to rotate the rudder if the axle is fitted in this position. Balanced rudders are of streamlined construction, which reduce drag.

Balanced Spade Rudder: A spade rudder is basically a rudder plate that is fixed to the rudder stock only at the top of the rudder. In other words, the rudder stock (or the axis of the rudder) does not run down along the span of the rudder. It is mainly used in vessels engaged on short voyages, such as ferries and Roll on–Roll off ships. The main disadvantage is that the total weight of the rudder is borne by the rudder bearing inside the hull of the vessel.

Flap Rudder: A Flap rudder is a high-lift rudder that produces more side force than a classic rudder of equivalent size. A flap rudder may be used to reduce the overall area of a rudder while maintaining the same rudder force or used whenever there is a requirement for high manoeuvrability. It consists of a blade with a trailing edge flap activated by a mechanical or hydraulic system, thus producing a variable flap angle as a function of the rudder angle.

Schilling Rudder (fishtail rudder): In the Schilling-type rudder, there is no flap, but the trailing edge is formed in a fishtail shape that accelerates the flow. The rudder angle, at the full helm position is 70°–75°, providing the vessel with great manoeuvrability to turn on its own axis. The build of the rudder is quite robust and with no moving parts it is relatively maintenance free, if compared to the rotor or flap types.

INTERACTION

What do you understand by interaction in respect to navigation? Explain different types of interactions with examples.

Interaction occurs when a ship comes too close to another ship or too close to a river or canal bank. Interaction is the reaction of the ship’s hull to pressure exerted on its underwater volume. The cause of the interaction is pressure bulbs that exist around the hull form of a moving ship.